The Age of the Goddess

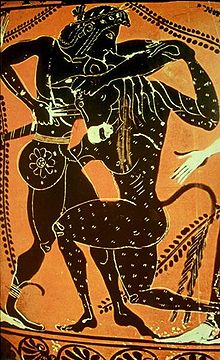

Theseus slays the Minotaur, Wikimedia Commons

The Consort of the Bull

The Mother of God

Can the Virgin Mary be the same as Venus-Aphrodite, or as Cybele, Hathor, Ishtar and Isis (to cite the most prominent)? The mother-bride of the dead and resurrected god, whose earliest known representations may be dated at least as early as about 5500 B.C. from archeological finds of statuettes of the mother-goddess in Turkey is the general theme, of which the above mentioned can be seen as local manifestations. The mythology of the mother of the dead and resurrected god has been known for millenniums to the neolithic and post-neolithic Levant.

Figurines of the mother-goddess are related to the Bronze Age myths and cults of the Great Goddess of many names, one of whose most celebrated temples stood precisely at Ephesus where – in the year 431 A.D. – the dogma of Mary as Theotokos (“Mother of God”) was proclaimed in Council. At that time the pagan religions of the Roman Empire were being suppressed, temples closed and destroyed, priests, philosophers and teachers banished and executed. From this time, Mary became the sole inheritor of all her predecessors in the Western world.

The Two Queens

The ancient civilization of Crete is of special importance in this context, since it represents the earliest high center of developed Bronze Age forms within the European sphere. The ruins of the palace of Knossos have contained such goddess-images in sealings dated about 1500 B.C. The high period of Cretan palaces was about 2500 – 1250 B.C., the same as that of the Indus Valley cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro.

In classical Greece, the mysteries of Eleusis are centered around the triad of Demeter (the mother-goddess Earth), Persephone (Queen of the Underworld), and the young god, their foster child Triptolemos (once a local king). A similar triad is found in the old Sumerian system with Inanna and Ereshkigal with Dumuzi (or his counterpart, the king in whom his spirit was incarnate). Between these two periods, a similar motif is found in an ivory plaque from the ruins of Mycenae. This triad of two queens and a king may be seen as a representation of this duality between the old Bronze Age mythology and the new patriarchal mythology of the Indo-Germanic invaders that gradually replaced it. Neither to the patriarchal Aryans nor to the patriarchal Semites belong the mystic, poetic themes of a paradise neither lost nor regained but ever present in the bosom of the goddess-mother – in whose being we have our death, as well as life, without fear.

The Mother of the Minotaur

In mythology, the serpent or the bull are usually symbolic of the power that fecundates the earth. In the sacrifices of the bull in Mesopotamia, the death of the bull was giving life to the creatures of the earth. A terra-cotta plaque from ancient Sumer places the Moon-Bull at the center of this process, where it appears as the ever-dying, ever-living lunar bull, consumed through all time by the lion-headed solar eagle. The bull has its foot on the earth, and is thus linked directly to the earth. The symbol here seems to represent the plane of juncture of earth and heaven, who appear to be two but are in being one. As we know from ancient Sumerian myth, heaven (An) and the earth (Ki) were in the beginning a single, undivided mountain (Anki), of which the lower part (the earth) was female and the upper (heaven) male. But the two were separated (as Adam into Adam and Eve) by their son Enlil (in the Bible by their “creator” Yahweh), whereupon the world of temporality appeared. The state of the ultimate bull is invisibility, that is to say pitch black (which is the color of the bulls that were used in the Mesopotamian rites).

The enigmatically blissful, impassive expression of the bull on the terra-cotta plaque appears again on the masklike figure of the Indian symbolic form of the Dancing Shiva. Shiva holds a drum in his lifted right hand, the drumbeat of time, the beat of creation, while on the palm of his left is the fire of the knowledge of immortality by which the bondages of time are destroyed. Shiva is the Lord of Beasts; so too is the great Sumerian lord of death and rebirth Dumuzi-Tammuz-Adonis, whose animal is this beatific bull; so too is the Greek God Dionysus, known – like Shiva – as the Cosmic Dancer, who is both the bull torn apart and the lion tearing.

In the mythology of the god-king Pharaoh of Egypt, he was called “the bull of his mother”. When dead within the mound of his tomb (the mound symbolic of the goddess), he was identified with Osiris begetting his son, and when alive, sitting on his throne (likewise symbolic of the goddess), he was the son of Osiris – Horus. These two, representing the whole mythic role of the dead yet reembodied King of the Universe, were in substance one. The cosmic cow-goddess Hathor (hat-hor: the house of Horus) stood upon the earth in such a way that her four legs were the pillars of the earth quarters and her belly was the firmament. The god Horus symbolized as a golden falcon, the sun, flying east to west, entered her mouth at the evening to be born again the next dawn. In this sense he was, in his night character, the “bull of his mother”, whereas by day – as a ruler of the world of light – he was a sharp-eyed bird of prey. Moreover, the animal of Osiris (the bull) was incarnate in the sacred Apis bull, which was ceremonially slain every twenty-five years – thus relieving the pharaoh himself of the obligation of a ritual regicide. (Ritual regicide was an integral part of ancient Sumerian and early Egyptian tradition.)

It may well be that the ritual game of the Cretan bull ring served the same function for the young god-kings of Crete. There are a number of representations of Cretan kings, and they always show a youth about twenty; there is none of an old man. So there may have been a regicide at the close of each Venus cycle. However, the prominence of the bull ring in the ritual art of Crete suggests that a ritual substitution may have been introduced at some time. In an old Cretan plaque there is the motive of a man-bull – a Minotaur – attacked by a man-lion. The analogy with the bull and lion-bird of Sumer seems clear. The lion as the animal of the blazing solar heat, slaying the bull as the animal of the moon by whose night dew the vegetation is restored. The matador with his sword, performing the same function as the lion-bird of Sumer, facing the bull in its role of the ever-dying, ever-living god: the lord of the goddess Earth (a role which in the classic Greek mythology was taken by Poseidon).

Cretan mythology has a preponderance of goddesses and female cult officiants, in contrast to the later Greek. The mythology of the Cretan world appears to represent an earlier stage of Bronze Age civilization than the kingly states of both Sumer and the Nile, which also sets them apart from these. It has a milder, gentler form, antecedent to the opening of the course of Eurasian history introduced by the wars and victory monuments of the self-interested kings. The invasions from the north and the east, with the Mycenaean heroic age of Agamemnon, Menelaus, Nestor and Odysseus, introduce the transition from the age of the goddess to the age of the warrior sons of god.

The Victory of the Sons of Light

In the new mythology of the great gods the attention has been shifted to the foreground figures of duality and combat, power, profit and loss, where the mind of the man of action normally dwells. Whereas the aim of the earlier mythology had been to support a state of indifference to the modalities of time and identification with the inhabiting non-dual mystery of all being, that of the new was just the opposite: to foster action in the field of time, where the subject and the object are two, separate and not the same. A is not B, death is not life, virtue is not vice, and the slayer is not the slain.

The best known mythic statement of this victory of the sun-god over the goddess and her spouse is the Babylonian epic of the victory of Marduk over his great-great-great-grandmother Tiamat, which appears to have been composed either in, or shortly following, the period of Hammurabi. The only existant document on this is from the library of King Ashurbanipal of Assyria (a millennium later (about 668 – 630 B.C.). Through this document we get an illustration of the gradual steps through which the transition from the matriarchal mythology to the patriarchal mythology took place:

1. The world born of a goddess without consort

2. The world born of a goddess fecundated by a consort

3. The world fashioned from the body of a goddess by a male warrior-god

4. The world created by the unaided power of a male god alone.

What, then, is the image of man’s fate that accompanies this great victory of the world of the patriarchal gods over that of the goddess-mother of the gods? The legend of Gilgamesh, by many termed the first great epic of the destiny of man, tells the tale.

Can the Virgin Mary be the same as Venus-Aphrodite, or as Cybele, Hathor, Ishtar and Isis (to cite the most prominent)? The mother-bride of the dead and resurrected god, whose earliest known representations may be dated at least as early as about 5500 B.C. from archeological finds of statuettes of the mother-goddess in Turkey is the general theme, of which the above mentioned can be seen as local manifestations. The mythology of the mother of the dead and resurrected god has been known for millenniums to the neolithic and post-neolithic Levant.

Figurines of the mother-goddess are related to the Bronze Age myths and cults of the Great Goddess of many names, one of whose most celebrated temples stood precisely at Ephesus where – in the year 431 A.D. – the dogma of Mary as Theotokos (“Mother of God”) was proclaimed in Council. At that time the pagan religions of the Roman Empire were being suppressed, temples closed and destroyed, priests, philosophers and teachers banished and executed. From this time, Mary became the sole inheritor of all her predecessors in the Western world.

The Two Queens

The ancient civilization of Crete is of special importance in this context, since it represents the earliest high center of developed Bronze Age forms within the European sphere. The ruins of the palace of Knossos have contained such goddess-images in sealings dated about 1500 B.C. The high period of Cretan palaces was about 2500 – 1250 B.C., the same as that of the Indus Valley cities of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro.

In classical Greece, the mysteries of Eleusis are centered around the triad of Demeter (the mother-goddess Earth), Persephone (Queen of the Underworld), and the young god, their foster child Triptolemos (once a local king). A similar triad is found in the old Sumerian system with Inanna and Ereshkigal with Dumuzi (or his counterpart, the king in whom his spirit was incarnate). Between these two periods, a similar motif is found in an ivory plaque from the ruins of Mycenae. This triad of two queens and a king may be seen as a representation of this duality between the old Bronze Age mythology and the new patriarchal mythology of the Indo-Germanic invaders that gradually replaced it. Neither to the patriarchal Aryans nor to the patriarchal Semites belong the mystic, poetic themes of a paradise neither lost nor regained but ever present in the bosom of the goddess-mother – in whose being we have our death, as well as life, without fear.

The Mother of the Minotaur

In mythology, the serpent or the bull are usually symbolic of the power that fecundates the earth. In the sacrifices of the bull in Mesopotamia, the death of the bull was giving life to the creatures of the earth. A terra-cotta plaque from ancient Sumer places the Moon-Bull at the center of this process, where it appears as the ever-dying, ever-living lunar bull, consumed through all time by the lion-headed solar eagle. The bull has its foot on the earth, and is thus linked directly to the earth. The symbol here seems to represent the plane of juncture of earth and heaven, who appear to be two but are in being one. As we know from ancient Sumerian myth, heaven (An) and the earth (Ki) were in the beginning a single, undivided mountain (Anki), of which the lower part (the earth) was female and the upper (heaven) male. But the two were separated (as Adam into Adam and Eve) by their son Enlil (in the Bible by their “creator” Yahweh), whereupon the world of temporality appeared. The state of the ultimate bull is invisibility, that is to say pitch black (which is the color of the bulls that were used in the Mesopotamian rites).

The enigmatically blissful, impassive expression of the bull on the terra-cotta plaque appears again on the masklike figure of the Indian symbolic form of the Dancing Shiva. Shiva holds a drum in his lifted right hand, the drumbeat of time, the beat of creation, while on the palm of his left is the fire of the knowledge of immortality by which the bondages of time are destroyed. Shiva is the Lord of Beasts; so too is the great Sumerian lord of death and rebirth Dumuzi-Tammuz-Adonis, whose animal is this beatific bull; so too is the Greek God Dionysus, known – like Shiva – as the Cosmic Dancer, who is both the bull torn apart and the lion tearing.

In the mythology of the god-king Pharaoh of Egypt, he was called “the bull of his mother”. When dead within the mound of his tomb (the mound symbolic of the goddess), he was identified with Osiris begetting his son, and when alive, sitting on his throne (likewise symbolic of the goddess), he was the son of Osiris – Horus. These two, representing the whole mythic role of the dead yet reembodied King of the Universe, were in substance one. The cosmic cow-goddess Hathor (hat-hor: the house of Horus) stood upon the earth in such a way that her four legs were the pillars of the earth quarters and her belly was the firmament. The god Horus symbolized as a golden falcon, the sun, flying east to west, entered her mouth at the evening to be born again the next dawn. In this sense he was, in his night character, the “bull of his mother”, whereas by day – as a ruler of the world of light – he was a sharp-eyed bird of prey. Moreover, the animal of Osiris (the bull) was incarnate in the sacred Apis bull, which was ceremonially slain every twenty-five years – thus relieving the pharaoh himself of the obligation of a ritual regicide. (Ritual regicide was an integral part of ancient Sumerian and early Egyptian tradition.)

It may well be that the ritual game of the Cretan bull ring served the same function for the young god-kings of Crete. There are a number of representations of Cretan kings, and they always show a youth about twenty; there is none of an old man. So there may have been a regicide at the close of each Venus cycle. However, the prominence of the bull ring in the ritual art of Crete suggests that a ritual substitution may have been introduced at some time. In an old Cretan plaque there is the motive of a man-bull – a Minotaur – attacked by a man-lion. The analogy with the bull and lion-bird of Sumer seems clear. The lion as the animal of the blazing solar heat, slaying the bull as the animal of the moon by whose night dew the vegetation is restored. The matador with his sword, performing the same function as the lion-bird of Sumer, facing the bull in its role of the ever-dying, ever-living god: the lord of the goddess Earth (a role which in the classic Greek mythology was taken by Poseidon).

Cretan mythology has a preponderance of goddesses and female cult officiants, in contrast to the later Greek. The mythology of the Cretan world appears to represent an earlier stage of Bronze Age civilization than the kingly states of both Sumer and the Nile, which also sets them apart from these. It has a milder, gentler form, antecedent to the opening of the course of Eurasian history introduced by the wars and victory monuments of the self-interested kings. The invasions from the north and the east, with the Mycenaean heroic age of Agamemnon, Menelaus, Nestor and Odysseus, introduce the transition from the age of the goddess to the age of the warrior sons of god.

The Victory of the Sons of Light

In the new mythology of the great gods the attention has been shifted to the foreground figures of duality and combat, power, profit and loss, where the mind of the man of action normally dwells. Whereas the aim of the earlier mythology had been to support a state of indifference to the modalities of time and identification with the inhabiting non-dual mystery of all being, that of the new was just the opposite: to foster action in the field of time, where the subject and the object are two, separate and not the same. A is not B, death is not life, virtue is not vice, and the slayer is not the slain.

The best known mythic statement of this victory of the sun-god over the goddess and her spouse is the Babylonian epic of the victory of Marduk over his great-great-great-grandmother Tiamat, which appears to have been composed either in, or shortly following, the period of Hammurabi. The only existant document on this is from the library of King Ashurbanipal of Assyria (a millennium later (about 668 – 630 B.C.). Through this document we get an illustration of the gradual steps through which the transition from the matriarchal mythology to the patriarchal mythology took place:

1. The world born of a goddess without consort

2. The world born of a goddess fecundated by a consort

3. The world fashioned from the body of a goddess by a male warrior-god

4. The world created by the unaided power of a male god alone.

What, then, is the image of man’s fate that accompanies this great victory of the world of the patriarchal gods over that of the goddess-mother of the gods? The legend of Gilgamesh, by many termed the first great epic of the destiny of man, tells the tale.