Joseph Campbell: Primitive Mythology

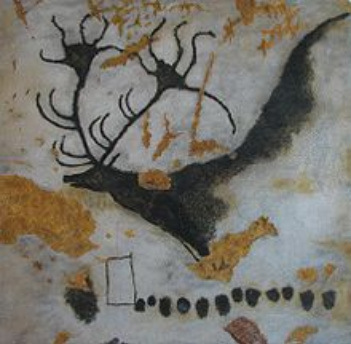

Lascaux, Megaloceros; Wikimedia Commons

Inherited images

and

Imprints of experience

Ritual enactments in primitive culture are real in the sense that the participants enter into the rites as if they are real situations. It is similar to how children, with their powers of imagination, enter totally into an imaginary world and experience it as reality – with the terrors and joys they entail. Belief is the first step to mythological seizure. The logic of cold, hard fact must not be allowed to intrude and remove the spell. The whole purpose of entering a sanctuary or participating in a festival is that one should be overtaken by the state known in India as “the other mind”.

Inherited images

The innate releasing mechanism (IRM) is understood as the inherited structure in the nervous system that enables an animal to respond in a certain way to a circumstance never experienced before. The factor triggering the response is termed a sign stimulus or a releaser.

A newly hatched chicken may fly for cover when a hawk flies past, but not when other birds pass. The inherited image of the enemy is already there in the nervous system, along with the appropriate reaction. A work of art picturing a hawk may do the same trick, as indicated on numerous large window panes to prevent birds from flying into the window.

C.G.Jung makes the distinction between the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious. The first is based on a context of forgotten, neglected or suppressed memory images derived from personal experience. The second is made up of what Jung terms archetypes. These are thought of as universal imprints found in each species, although in different forms in each species, that contain accumulated experiences and emotions resulting in typical patterns of behavior when given sign stimuli appear. Jung compared these archetypes to the Platonic ideas (pure mental forms imprinted in the soul before it was born into the world. They were seen as collective in the sense that they embodied the fundamental characteristics of a thing rather than its specific peculiarities in given cases).

In the central nervous system of all animals there exist innate structures that are somehow counterparts of the proper environment of the species. The animal, directed by innate endowment, comes to terms with its natural environment not as a consequence of any long, slow learning through experience, through trial and error, but immediately and with the certainty of recognition.

Although in many instances the sign stimuli that release animal response are immutable and correspond to the inner readiness of that animal, there are also systems of response that are established by individual experience. In these cases, the IRM is described as open, susceptible to “impression” or “imprint”. Where these “open structures” exist, the first imprint is definitive, requires sometimes less than a minute for its completion, and is irreversible.

Among humans we know the expression “you have only one chance to make a first impression”, and we also know how hard it is for us to modify our first impression. It never leaves us, but later experience may – with the effort of our intellect (which animals do not have in the same way) – allow us to get a total impression which may differ from the first impression. The entire instinct structure of man is much more open to learning and conditioning than that of animals.

Whereas animals are fully developed very quickly after birth, humans are under constant development and subject to the pressures and imprints of society during their long maturation process. In this sense, humans are born prematurely. Because of this prematurity we have a more open reflex structure than animals, we are less rigidly patterned in our instincts, less conservative, dependable and secure than they are. Our brain being three times as great in size as that of our nearest rival, we have, however, acquired a greater capacity to control and inhibit our responses. This immaturity that we are born with has enabled us to retain the capacity to play.

Imprints of experience

Joseph Campbell cites James Joyce (from “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man”) as supplying an excellent structuring principle for a cross-cultural study of mythology when Joyce defines the material of tragedy as “whatsoever is grave and constant in human sufferings”.

Comparative mythology is a study of the attributes of being, through which the human mind has been united with the secret cause in tragic terror and with the human sufferer in tragic pity. These attributes of being are of two orders: those inevitably deriving from the primary conditions of all human experience whatsoever, and those particular to the various areas and eras of human civilization. However, suffering is not the central theme. The paramount theme of mythology is not the agony of quest, but the rapture of a revelation. Suffering itself is a deception; its core is rapture, which is the attribute of illumination. The imprint of rapture enclosed in suffering is the foremost “grave and constant” in this context.

Dawn and awakening, sun and sunrise; moon and darkness, and light dispelling fears of night represent a polarity that must be reckoned as inevitable in the way of a structuring principle of human thought. The fundamental notion of a life-structuring relationship between the heavenly world and that of man was derived from the realization of the force of the lunar cycle.

The relation between male and female is surely another universal of human experience. The mysterious functioning of the female body in its menstrual cycle, in the ceasing of the cycle during the period of gestation, and in the agony of birth – and the appearance then of a new being – have all made profound imprints on the mind.

The stages of life – childhood and youth, maturity, and old age – give us yet another deep structuring imprint. The imprints of early infancy are the source of many of the most widely known images of myth. Firstly, the birth trauma - an archetype of transformation – evocates the brief moment of loss of security and threat of death that accompanies any crisis of radical change.

The water image in mythology is intimately associated with this motif, and the goddesses, mermaids, witches, and sirens that often appear as guardians or manifestations of water, may represent either its life-threatening or its life-furthering aspect. Water is the vehicle of the power of the goddess, and she personifies the mystery of waters of birth and dissolution. This manner of moving between the personal and the universal is basic to mythological discourse.

The next constellation of imprints to be noted is that associated with the bliss of the child at the mother’s breast. The relationship of suckling to mother is one of symbiosis. When the mother image begins to assume definition in the gradual dawn of the infantile consciousness, it is already associated not only with a sense of beatitude, but also with fantasies of danger, separation and terrible destruction. Cannibal ogresses appear in the folklore of peoples throughout the world, as exemplified by the Hindu goddess Kali, the “Black One”, who is a personification of “all-consuming Time”, or in the medieval European figure of the consumer of the wicked dead, the female mouth and belly of Hel.

The labyrinth, maze, and spiral were associated in ancient Crete and Babylon with the internal organs of the human anatomy as well as with the underworld, the one being the microcosm of the other. The object of the tomb builder would have been to make the tomb as much like the body of the mother as he was able, since to enter the next world the spirit would have to be re-born. Two ideas are involved: the idea of defence and exclusion, and the idea of the penetration, on correct terms, of this defence. The overcoming of these difficulties by a hero frequently precedes union with some hidden princess. The myth of Theseus, Ariadne and the Cretan labyrinth is one example. Aeneas, seeing a figure of the Cretan labyrinth at the cavern-entrance of the underworld and being helped to enter by the Sibyl, is another.

A third system of imprints that can be assumed to be universal in the development of the infant is that deriving from its fascination with its own excrement, which becomes strong at the age of about two and a half. For the child, at this period of life, defecation is experienced as a creative act. Normally, the child’s enthusiasm is repressed by higher authority. However, this imprint, as a forbidden image, then stays vivid in the child’s imagination. There is abundant evidence of dualistic systems of imagery deriving from this circumstance, recognized in the prevalence of an association of filth with sin and cleanliness with virtue.

A fourth group of imprints engraved on the psyche of the infant, appears when the physical difference between the sexes becomes a matter of keen concern. In the masculine imagination all fear of punishment is linked to an obscurely sensed castration fear, while the female is obsessed with an envy that cannot be quite quenched until she has brought forth a son from her own body. In the male, the sense of her dangerous envy is ever present, and tends to be associated with the image of the ogress and cannibal witch. In certain primitive mythologies there is a motif known as “the toothed vagina” – the vagina that castrates. A counterpart, the other way, is the so-called “phallic mother”.

A fifth and culminating syndrome of imprints of this kind, is that of the long and variously argued Oedipus complex. The claim for the universality of this complex has been challenged by a number of anthropologists, but facts indicate that the youngster (Oedipus comlex for the boy and legend of Electra for the girl) at the age of five or six becomes implicated imaginatively in a “family romance” – the boy with his mother and the girl with her father, with the father and the mother respectively being looked at as rivals.

It is only relatively slowly that a notion of individual freedom and sense of independence are developed. This process of dissociation may lead to a sense of self-sufficiency and an order of logic in which subjective and objective are rationally kept apart. It may also lead to a deterioration of the unity of the social order and to a sense of separateness which may end in a general atmosphere of anxiety and neurosis.

It has been one of the chief aims of all religious teaching and ceremonial, therefore, to suppress as much as possible the sense of ego and develop that of participation. Such participation, in primitive cults, is principally in the organism of the community, which itself is conceived as participating in the natural order of the local environment.

The figure of a creative being is practically, if not absolutely, universal in the mythologies of the world. Just as the parental image is associated in childhood not only with the power to make all things, but also with the authority to command, so also in religious thought the creator of the universe is commonly the giver and controller of its laws. The two orders – the infantile and the religious – are at least analogous, and it may well be that the latter is simply a translation of the former to a sphere out of range of critical observation.

The sense, then, of this world as an undifferentiated continuum of simultaneously subjective and objective experience (participation), which is alive (animism), and which was produced by some superior being (artificialism), may be said to constitute the axiomatic, spontaneously supposed frame of reference of all childhood experience – no matter what the local specificities of this experience may happen to be. And these three principles are precisely those most generally represented in the mythologies and religious systems of the whole world.

The transformation of the child into the adult, which in higher societies is achieved through years of education, is accomplished on the primitive level more briefly and abruptly by means of the puberty rites. These rites contain the requirements of the local group, and they are made in such a way as to inculcate the sentiments of the local system of thought. From culture to culture, the sign symbols presented in the rites of initiation differ considerably, and they therefore have to be studied from a historical as well as from a psychological point of view.

It is possible that the failure of mythology and ritual to function effectively in our civilization may account for the high incidence among us of the malaise that has lead to the characterization of our time as “The Age of Anxiety”. The Ego, dissociated from identification with the group, generates fear and desire, and it is only after the concept of “I” has been established that the fear of one’s own destruction or one’s own desires can develop.

As old age comes, the notion of the underworld as a realm of the dead, entered by a cleft or burrow in the earth, associated with the themes of the labyrinth and abyss of water, is frequent in mythology. This reactivates the old context of the dear but frightening mother womb and the terrible father. Does this give more depth to the old expression of “second childhood”? Is this a universal imprint? The considerable mutual attraction of the very young and the very old may derive something from their common, secret knowledge that it is they, and not the busy generation between, who are concerned with a poetic play that is eternal and truly wise.

Two contrasting images of death have fashioned two contrasting worlds of myth: that of the primitive hunters, deriving from the impact, imprint, of life and death in the animal sphere; and that of the primitive planters, derived from the model of the cycle of death and rebirth in the plant. A further exploration of these two worlds is given when we look at the mythology of the primitive hunters and that of the primitive planters.

Inherited images

The innate releasing mechanism (IRM) is understood as the inherited structure in the nervous system that enables an animal to respond in a certain way to a circumstance never experienced before. The factor triggering the response is termed a sign stimulus or a releaser.

A newly hatched chicken may fly for cover when a hawk flies past, but not when other birds pass. The inherited image of the enemy is already there in the nervous system, along with the appropriate reaction. A work of art picturing a hawk may do the same trick, as indicated on numerous large window panes to prevent birds from flying into the window.

C.G.Jung makes the distinction between the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious. The first is based on a context of forgotten, neglected or suppressed memory images derived from personal experience. The second is made up of what Jung terms archetypes. These are thought of as universal imprints found in each species, although in different forms in each species, that contain accumulated experiences and emotions resulting in typical patterns of behavior when given sign stimuli appear. Jung compared these archetypes to the Platonic ideas (pure mental forms imprinted in the soul before it was born into the world. They were seen as collective in the sense that they embodied the fundamental characteristics of a thing rather than its specific peculiarities in given cases).

In the central nervous system of all animals there exist innate structures that are somehow counterparts of the proper environment of the species. The animal, directed by innate endowment, comes to terms with its natural environment not as a consequence of any long, slow learning through experience, through trial and error, but immediately and with the certainty of recognition.

Although in many instances the sign stimuli that release animal response are immutable and correspond to the inner readiness of that animal, there are also systems of response that are established by individual experience. In these cases, the IRM is described as open, susceptible to “impression” or “imprint”. Where these “open structures” exist, the first imprint is definitive, requires sometimes less than a minute for its completion, and is irreversible.

Among humans we know the expression “you have only one chance to make a first impression”, and we also know how hard it is for us to modify our first impression. It never leaves us, but later experience may – with the effort of our intellect (which animals do not have in the same way) – allow us to get a total impression which may differ from the first impression. The entire instinct structure of man is much more open to learning and conditioning than that of animals.

Whereas animals are fully developed very quickly after birth, humans are under constant development and subject to the pressures and imprints of society during their long maturation process. In this sense, humans are born prematurely. Because of this prematurity we have a more open reflex structure than animals, we are less rigidly patterned in our instincts, less conservative, dependable and secure than they are. Our brain being three times as great in size as that of our nearest rival, we have, however, acquired a greater capacity to control and inhibit our responses. This immaturity that we are born with has enabled us to retain the capacity to play.

Imprints of experience

Joseph Campbell cites James Joyce (from “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man”) as supplying an excellent structuring principle for a cross-cultural study of mythology when Joyce defines the material of tragedy as “whatsoever is grave and constant in human sufferings”.

Comparative mythology is a study of the attributes of being, through which the human mind has been united with the secret cause in tragic terror and with the human sufferer in tragic pity. These attributes of being are of two orders: those inevitably deriving from the primary conditions of all human experience whatsoever, and those particular to the various areas and eras of human civilization. However, suffering is not the central theme. The paramount theme of mythology is not the agony of quest, but the rapture of a revelation. Suffering itself is a deception; its core is rapture, which is the attribute of illumination. The imprint of rapture enclosed in suffering is the foremost “grave and constant” in this context.

Dawn and awakening, sun and sunrise; moon and darkness, and light dispelling fears of night represent a polarity that must be reckoned as inevitable in the way of a structuring principle of human thought. The fundamental notion of a life-structuring relationship between the heavenly world and that of man was derived from the realization of the force of the lunar cycle.

The relation between male and female is surely another universal of human experience. The mysterious functioning of the female body in its menstrual cycle, in the ceasing of the cycle during the period of gestation, and in the agony of birth – and the appearance then of a new being – have all made profound imprints on the mind.

The stages of life – childhood and youth, maturity, and old age – give us yet another deep structuring imprint. The imprints of early infancy are the source of many of the most widely known images of myth. Firstly, the birth trauma - an archetype of transformation – evocates the brief moment of loss of security and threat of death that accompanies any crisis of radical change.

The water image in mythology is intimately associated with this motif, and the goddesses, mermaids, witches, and sirens that often appear as guardians or manifestations of water, may represent either its life-threatening or its life-furthering aspect. Water is the vehicle of the power of the goddess, and she personifies the mystery of waters of birth and dissolution. This manner of moving between the personal and the universal is basic to mythological discourse.

The next constellation of imprints to be noted is that associated with the bliss of the child at the mother’s breast. The relationship of suckling to mother is one of symbiosis. When the mother image begins to assume definition in the gradual dawn of the infantile consciousness, it is already associated not only with a sense of beatitude, but also with fantasies of danger, separation and terrible destruction. Cannibal ogresses appear in the folklore of peoples throughout the world, as exemplified by the Hindu goddess Kali, the “Black One”, who is a personification of “all-consuming Time”, or in the medieval European figure of the consumer of the wicked dead, the female mouth and belly of Hel.

The labyrinth, maze, and spiral were associated in ancient Crete and Babylon with the internal organs of the human anatomy as well as with the underworld, the one being the microcosm of the other. The object of the tomb builder would have been to make the tomb as much like the body of the mother as he was able, since to enter the next world the spirit would have to be re-born. Two ideas are involved: the idea of defence and exclusion, and the idea of the penetration, on correct terms, of this defence. The overcoming of these difficulties by a hero frequently precedes union with some hidden princess. The myth of Theseus, Ariadne and the Cretan labyrinth is one example. Aeneas, seeing a figure of the Cretan labyrinth at the cavern-entrance of the underworld and being helped to enter by the Sibyl, is another.

A third system of imprints that can be assumed to be universal in the development of the infant is that deriving from its fascination with its own excrement, which becomes strong at the age of about two and a half. For the child, at this period of life, defecation is experienced as a creative act. Normally, the child’s enthusiasm is repressed by higher authority. However, this imprint, as a forbidden image, then stays vivid in the child’s imagination. There is abundant evidence of dualistic systems of imagery deriving from this circumstance, recognized in the prevalence of an association of filth with sin and cleanliness with virtue.

A fourth group of imprints engraved on the psyche of the infant, appears when the physical difference between the sexes becomes a matter of keen concern. In the masculine imagination all fear of punishment is linked to an obscurely sensed castration fear, while the female is obsessed with an envy that cannot be quite quenched until she has brought forth a son from her own body. In the male, the sense of her dangerous envy is ever present, and tends to be associated with the image of the ogress and cannibal witch. In certain primitive mythologies there is a motif known as “the toothed vagina” – the vagina that castrates. A counterpart, the other way, is the so-called “phallic mother”.

A fifth and culminating syndrome of imprints of this kind, is that of the long and variously argued Oedipus complex. The claim for the universality of this complex has been challenged by a number of anthropologists, but facts indicate that the youngster (Oedipus comlex for the boy and legend of Electra for the girl) at the age of five or six becomes implicated imaginatively in a “family romance” – the boy with his mother and the girl with her father, with the father and the mother respectively being looked at as rivals.

It is only relatively slowly that a notion of individual freedom and sense of independence are developed. This process of dissociation may lead to a sense of self-sufficiency and an order of logic in which subjective and objective are rationally kept apart. It may also lead to a deterioration of the unity of the social order and to a sense of separateness which may end in a general atmosphere of anxiety and neurosis.

It has been one of the chief aims of all religious teaching and ceremonial, therefore, to suppress as much as possible the sense of ego and develop that of participation. Such participation, in primitive cults, is principally in the organism of the community, which itself is conceived as participating in the natural order of the local environment.

The figure of a creative being is practically, if not absolutely, universal in the mythologies of the world. Just as the parental image is associated in childhood not only with the power to make all things, but also with the authority to command, so also in religious thought the creator of the universe is commonly the giver and controller of its laws. The two orders – the infantile and the religious – are at least analogous, and it may well be that the latter is simply a translation of the former to a sphere out of range of critical observation.

The sense, then, of this world as an undifferentiated continuum of simultaneously subjective and objective experience (participation), which is alive (animism), and which was produced by some superior being (artificialism), may be said to constitute the axiomatic, spontaneously supposed frame of reference of all childhood experience – no matter what the local specificities of this experience may happen to be. And these three principles are precisely those most generally represented in the mythologies and religious systems of the whole world.

The transformation of the child into the adult, which in higher societies is achieved through years of education, is accomplished on the primitive level more briefly and abruptly by means of the puberty rites. These rites contain the requirements of the local group, and they are made in such a way as to inculcate the sentiments of the local system of thought. From culture to culture, the sign symbols presented in the rites of initiation differ considerably, and they therefore have to be studied from a historical as well as from a psychological point of view.

It is possible that the failure of mythology and ritual to function effectively in our civilization may account for the high incidence among us of the malaise that has lead to the characterization of our time as “The Age of Anxiety”. The Ego, dissociated from identification with the group, generates fear and desire, and it is only after the concept of “I” has been established that the fear of one’s own destruction or one’s own desires can develop.

As old age comes, the notion of the underworld as a realm of the dead, entered by a cleft or burrow in the earth, associated with the themes of the labyrinth and abyss of water, is frequent in mythology. This reactivates the old context of the dear but frightening mother womb and the terrible father. Does this give more depth to the old expression of “second childhood”? Is this a universal imprint? The considerable mutual attraction of the very young and the very old may derive something from their common, secret knowledge that it is they, and not the busy generation between, who are concerned with a poetic play that is eternal and truly wise.

Two contrasting images of death have fashioned two contrasting worlds of myth: that of the primitive hunters, deriving from the impact, imprint, of life and death in the animal sphere; and that of the primitive planters, derived from the model of the cycle of death and rebirth in the plant. A further exploration of these two worlds is given when we look at the mythology of the primitive hunters and that of the primitive planters.