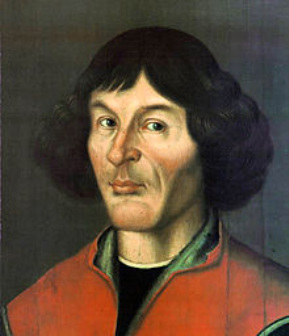

Nicolaus Copernicus; Wikimedia Commons

The Philosophy of the 1500s

In the 16th century the Renaissance came into full flower. The word “Renaissance”, from French, means rebirth, and this term was chosen to reflect a movement back to the emphasis on the individual in the thinking found in Antiquity – combined with the liberation of thought from the normative dogmas of the Church in the Middle Ages. Nature, science, arts and individual achievement came to the forefront of public attention. This development did not imply a break with the role of the Church, but – although the Church retained much of its political power – it opened the door for increased freedom of thought, expression and action. Leonardo da Vinci (1452 - 1519) and Pico della Mirandola (1463 - 1494) were important figures in this context in the Renaissance in Italy, where the movement gained momentum in the 1400s.

Among the developments in philosophical thinking in this period, the major ones took place in cosmological thinking. Nicolaus Copernicus (1473 – 1543) established the heliocentric view of the movements of planets, at the expense of the old geocentric view held by the Church. His views were supported and expanded upon by Giordano Bruno (1548 – 1600), who was burned at the Campo dei Fiori in Roma by the Inquisition for his opinions (thus showing that there still was some way to go before freedom of speech was established). Later, Johannes Kepler (1571 - 1630), developed more precise theories of the elliptic movements of the planets – which he could confirm by using the observations made by Tycho Brahe (1546 – 1601), made available to Kepler after Brahe’s death.

In other fields of work, important philosophical thinkers in this period were Nicolo Machiavelli (1469 – 1527) and Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626). They both emphasized the importance of empirical observation as the basis for the search of truth. Ideas alone could not lead to truth, unless supported by empirical facts. Machiavelli’s empirical attitude has often been labeled cynicism, because his field of study was the behavior to be adopted by political leaders seeking power. Francis Bacon’s attention was directed to science, and his views preceded those of the so-called empiricists of the 18th century. More will be said on Bacon below (under the heading of the 1600s).

Among the developments in philosophical thinking in this period, the major ones took place in cosmological thinking. Nicolaus Copernicus (1473 – 1543) established the heliocentric view of the movements of planets, at the expense of the old geocentric view held by the Church. His views were supported and expanded upon by Giordano Bruno (1548 – 1600), who was burned at the Campo dei Fiori in Roma by the Inquisition for his opinions (thus showing that there still was some way to go before freedom of speech was established). Later, Johannes Kepler (1571 - 1630), developed more precise theories of the elliptic movements of the planets – which he could confirm by using the observations made by Tycho Brahe (1546 – 1601), made available to Kepler after Brahe’s death.

In other fields of work, important philosophical thinkers in this period were Nicolo Machiavelli (1469 – 1527) and Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626). They both emphasized the importance of empirical observation as the basis for the search of truth. Ideas alone could not lead to truth, unless supported by empirical facts. Machiavelli’s empirical attitude has often been labeled cynicism, because his field of study was the behavior to be adopted by political leaders seeking power. Francis Bacon’s attention was directed to science, and his views preceded those of the so-called empiricists of the 18th century. More will be said on Bacon below (under the heading of the 1600s).