The Primitive Hunters

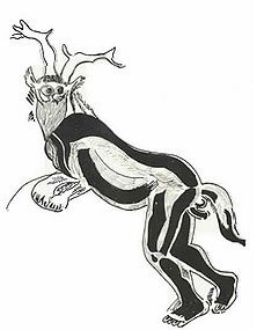

The Sorcerer of the 'Trois Frères' ; Wikimedia Commons

Shamanism

Shamanism

The shaman and the priest.

Among the Indians of North America two contrasting mythologies appear, according to whether tribes are hunters or planters.

Those that are primarily hunters emphasize in their religious life the individual fast for the gaining of visions. The boy of twelve or thirteen is left by his father in some lonesome place, with a little fire to keep the beasts away. There he fasts and prays, four days or more, until some spiritual visitant comes in dream, in human or animal form, to speak to him and give him power. His later career will be determined by this vision. He may be conferred the power to cure people as a shaman, the power to attract and slaughter animals, or the ability to become a warrior. If the career supplied by this vision is not sufficient for the ambitions of the boy, he may fast again, as often as he likes.

Among the planting tribes – the Hopi, Zuñi, and other Pueblo dwellers – life is organized around the rich and complex ceremonies of their masked gods. These are elaborate rites in which the whole community participates, scheduled according to a religious calendar and conducted by societies of trained priests. In such a society there is little room for individual play. There is a rigid relationship not only of the individual to his fellows, but also of village life to the calendric cycle; for the planters are intensely aware of their dependency upon the gods of the elements.

For the hunter, hunter’s luck is a very different thing. The contrast between the two world views may be seen by comparing the priest and the shaman. The priest is the socially initiated, ceremonially inducted member of a recognized religious organization, where he holds a certain rank and functions as the tenant of an office that was held by others before him. The shaman is one who, as a consequence of a personal psychological crisis, has gained a certain power of his own. The spiritual visitants who came to him in vision had never been seen before by any other; they were his particular familiars and protectors. The masked gods of the Pueblos, on the other hand, the corn gods, and the cloud gods, served by societies of strictly organized and very orderly priests, are the well known patrons of the entire village.

In the origin legend of the Jicarilla Apache Indians of New Mexico there is an excellent illustration of the capitulation of the style of religiosity represented by the shamanism of a hunting tribe to the greater force of the more stable, socially organized and maintained priestly order of a planting-culture complex. In their creation myth, the Hactcin are the Apache counterparts of the masked gods of the Pueblo villages. Their most powerful god, the Black Hactcin, challenges the shamans to show their powers – because the shamans have boasted that they have the power to make the sun and the moon appear or disappear. The shamans then do all sorts of impressive tricks, but the tricks have no effect on the sun and the moon. The Black Hactcin then calls forth all the different creatures he has created and through planting ceremonies they make the sun appear. The Black Hactcin then selected twelve shamans who had been particularly spectacular and painted six of them in blue all over, to represent the summer season, and six white, to represent winter. He called them Tsanati, and this was the origin of the Tsanati dance society of the Jicarilla Apache. The shamans were thus integrated in the mythology, but subordinated to the planting culture.

Mythological flux in the meeting between hunting and planting cultures

This type of myth, where the mythology of one group absorbs the other, is found in all places where cultural transformation takes place – either because of evolution or because of changes in power structure arising from migration or other forms of conflict. The mythologies of the Hindus, Persians, Greeks, Celts and Germans give many examples of this, as for instance in the tales of the conquest of the titans by the gods. The titans were overthrown, pinned beneath mountains, and exiled to the rugged regions at the bounds of the earth, and as long as the power of the gods can keep them there, the people, the animals, and all living things will know the blessings of a world ruled by law.

The highest concern of all the mythologies, ceremonials, ethical systems, and social organizations of the agriculturally based societies has been that of suppressing the manifestations of individualism, and compelling people to identify themselves with the archetypes of behavior and systems of sentiment in the public domain. Every impulse to self-discovery has been purged away. However, there have always been those who have very much wished to remain alone, achieving sometimes that solitude in which the Great Spirit, the Power, the Great Mystery that is hidden from the group in its concerns, gives a special force to this individual. Like an eagle the spirit then soars on its own wings. The dragon “Thou shalt”, as Nietzsche terms the social fiction of the moral law, has then been slain by the lion of self-discovery.

This then, is an important distinction between the mythologies of the hunters and those of the planters: the accent of the planting rites is on the group, while that of the hunters is on the individual (though the group does not disappear here neither). In the world of the hunt, the shamanistic principle preponderates and the mythological and ritual life is far less richly developed than among the planters. Most of its functioning deities are rather in the nature of personal familiars than of profoundly developed gods.

Shamanistic magic.

The magic powers acquired by the shamans are such that when they appear among their tribesmen, there is an element of fear among the members of the tribe. Reciprocally, the shamans themselves have always lived in fear of their communities, because they never can know when the tribal fear will turn into aggression against the shaman. Adding to this vulnerability of the shaman, he (or she, since a shaman can also be a woman) will often be the chief target for being killed by enemy tribes whenever tribal warfare is on.

The shamans are the particular guardians and reciters of the chants and traditions of their people. The shamanistic visions spring from the crisis in the period of formation of the shaman. This crisis, and the subsequent ordeals that the shaman subjects himself to during his formation, creates a person of great physical stamina and vitality of spirit. The superior intelligence and refinement that in addition often characterizes him, in sum yields a person who stands out remarkably from the normal members of the tribe.

The group rites of the hunting societies are basically precipitations into the public field of images first experienced in shamanistic vision. These rites are rendering myths best known to shamans and best interpreted by shamans: the painful crisis of the deeply forced vocational call carries the young adept to the root not only of his cultural structure, but also of the psychological structures of every member of his tribe.

A structuring theme is death and resurrection. The vision of the tree is another important element in shamanism. Like the tree of Wotan, Yggdrasil, it is the world axis, reaching to the zenith. The shaman has been nurtured in this tree, and his drum - fashioned of its wood – bears him back to it in his trance of ecstasy. The shaman’s power rests in his ability to throw himself into a trance at will. He is not the victim of his trance; he commands it as a bird the air in its flight. The magic of his drum carries him away on the wings of its rhythm, the wings of spiritual transport. While in his trance he is flying as a bird to the upper world, or descending as a reindeer, bull or bear to the world beneath.

The basic form of the shamanistic crisis can be summarized as follows: firstly, a spontaneously precipitated rupture with the world of common day, revealed in symptoms analogous to those of a serious nervous breakdown (visions of dismemberment, fosterage in the world of the spirits, and restitution). Secondly, a course of shamanistic, mythological instruction under a master, through which an actual restitution of a superior level is achieved. Thirdly, a career of magical practice in the service of the community, defended from the natural resentment of the assisted community by various tricks and parodies of power.

The Fire-Bringer.

The figure of the trickster appears to have been the chief mythological character of the world of story. He appeared under many guises, both animal and human. He is the culture-bringer, but also the epitome of the principle of disorder. In the Paleolithic sphere from which this figure derives, he was the archetype of the hero, the giver of all great boons – the fire-bringer and the teacher of mankind. Beyond the ethical dualism of god and devil, the trickster shows the creative force in its primary innocence. The hunting tribes of North America attribute the same shamanistic earth-fashioning deed to their Paleolithic hero-trickster.

Paleolithic mythology and The Animal Master.

Legends of hunting tribes, supported by evidence found in the Paleolithic caves of southern France (dating back to about 30 000 B.C.), give indications of several clues of particular importance to understanding Paleolithic mythology.

Firstly, the action is not placed in an earlier mythological age, but in a world like their present world. Where shamanism is involved, the mythological age and realm are here and now. Secondly, a central figure is a bird (magpie) without whose work as intermediary nothing could have been accomplished. This bird symbolizes the shaman-trickster, whose social function in the tribe was to serve as the intermediary between man and the powers behind the veil of nature. Thirdly, a dead man’s return to life is made possible by the finding of a particle of bone. Fourthly, the game animals when being chased to a fall and actually going over it, are acting under the influence of the animal master. Fifthly, when the animals - under the influence of the animal master – went over the fall, their flesh is to be regarded as the willed gift of that master to the people. Sixthly, there is a right way and a wrong way to kill animals. When the animal rites are properly celebrated by the people, there is a magical accord between the animals and those who have to hunt them. The hunt itself is a rite of sacrifice, and the proper sacrifice is the animal itself, which through its death and return represents a permanent process in the shadow world of accident and chance.

Among the Indians of North America two contrasting mythologies appear, according to whether tribes are hunters or planters.

Those that are primarily hunters emphasize in their religious life the individual fast for the gaining of visions. The boy of twelve or thirteen is left by his father in some lonesome place, with a little fire to keep the beasts away. There he fasts and prays, four days or more, until some spiritual visitant comes in dream, in human or animal form, to speak to him and give him power. His later career will be determined by this vision. He may be conferred the power to cure people as a shaman, the power to attract and slaughter animals, or the ability to become a warrior. If the career supplied by this vision is not sufficient for the ambitions of the boy, he may fast again, as often as he likes.

Among the planting tribes – the Hopi, Zuñi, and other Pueblo dwellers – life is organized around the rich and complex ceremonies of their masked gods. These are elaborate rites in which the whole community participates, scheduled according to a religious calendar and conducted by societies of trained priests. In such a society there is little room for individual play. There is a rigid relationship not only of the individual to his fellows, but also of village life to the calendric cycle; for the planters are intensely aware of their dependency upon the gods of the elements.

For the hunter, hunter’s luck is a very different thing. The contrast between the two world views may be seen by comparing the priest and the shaman. The priest is the socially initiated, ceremonially inducted member of a recognized religious organization, where he holds a certain rank and functions as the tenant of an office that was held by others before him. The shaman is one who, as a consequence of a personal psychological crisis, has gained a certain power of his own. The spiritual visitants who came to him in vision had never been seen before by any other; they were his particular familiars and protectors. The masked gods of the Pueblos, on the other hand, the corn gods, and the cloud gods, served by societies of strictly organized and very orderly priests, are the well known patrons of the entire village.

In the origin legend of the Jicarilla Apache Indians of New Mexico there is an excellent illustration of the capitulation of the style of religiosity represented by the shamanism of a hunting tribe to the greater force of the more stable, socially organized and maintained priestly order of a planting-culture complex. In their creation myth, the Hactcin are the Apache counterparts of the masked gods of the Pueblo villages. Their most powerful god, the Black Hactcin, challenges the shamans to show their powers – because the shamans have boasted that they have the power to make the sun and the moon appear or disappear. The shamans then do all sorts of impressive tricks, but the tricks have no effect on the sun and the moon. The Black Hactcin then calls forth all the different creatures he has created and through planting ceremonies they make the sun appear. The Black Hactcin then selected twelve shamans who had been particularly spectacular and painted six of them in blue all over, to represent the summer season, and six white, to represent winter. He called them Tsanati, and this was the origin of the Tsanati dance society of the Jicarilla Apache. The shamans were thus integrated in the mythology, but subordinated to the planting culture.

Mythological flux in the meeting between hunting and planting cultures

This type of myth, where the mythology of one group absorbs the other, is found in all places where cultural transformation takes place – either because of evolution or because of changes in power structure arising from migration or other forms of conflict. The mythologies of the Hindus, Persians, Greeks, Celts and Germans give many examples of this, as for instance in the tales of the conquest of the titans by the gods. The titans were overthrown, pinned beneath mountains, and exiled to the rugged regions at the bounds of the earth, and as long as the power of the gods can keep them there, the people, the animals, and all living things will know the blessings of a world ruled by law.

The highest concern of all the mythologies, ceremonials, ethical systems, and social organizations of the agriculturally based societies has been that of suppressing the manifestations of individualism, and compelling people to identify themselves with the archetypes of behavior and systems of sentiment in the public domain. Every impulse to self-discovery has been purged away. However, there have always been those who have very much wished to remain alone, achieving sometimes that solitude in which the Great Spirit, the Power, the Great Mystery that is hidden from the group in its concerns, gives a special force to this individual. Like an eagle the spirit then soars on its own wings. The dragon “Thou shalt”, as Nietzsche terms the social fiction of the moral law, has then been slain by the lion of self-discovery.

This then, is an important distinction between the mythologies of the hunters and those of the planters: the accent of the planting rites is on the group, while that of the hunters is on the individual (though the group does not disappear here neither). In the world of the hunt, the shamanistic principle preponderates and the mythological and ritual life is far less richly developed than among the planters. Most of its functioning deities are rather in the nature of personal familiars than of profoundly developed gods.

Shamanistic magic.

The magic powers acquired by the shamans are such that when they appear among their tribesmen, there is an element of fear among the members of the tribe. Reciprocally, the shamans themselves have always lived in fear of their communities, because they never can know when the tribal fear will turn into aggression against the shaman. Adding to this vulnerability of the shaman, he (or she, since a shaman can also be a woman) will often be the chief target for being killed by enemy tribes whenever tribal warfare is on.

The shamans are the particular guardians and reciters of the chants and traditions of their people. The shamanistic visions spring from the crisis in the period of formation of the shaman. This crisis, and the subsequent ordeals that the shaman subjects himself to during his formation, creates a person of great physical stamina and vitality of spirit. The superior intelligence and refinement that in addition often characterizes him, in sum yields a person who stands out remarkably from the normal members of the tribe.

The group rites of the hunting societies are basically precipitations into the public field of images first experienced in shamanistic vision. These rites are rendering myths best known to shamans and best interpreted by shamans: the painful crisis of the deeply forced vocational call carries the young adept to the root not only of his cultural structure, but also of the psychological structures of every member of his tribe.

A structuring theme is death and resurrection. The vision of the tree is another important element in shamanism. Like the tree of Wotan, Yggdrasil, it is the world axis, reaching to the zenith. The shaman has been nurtured in this tree, and his drum - fashioned of its wood – bears him back to it in his trance of ecstasy. The shaman’s power rests in his ability to throw himself into a trance at will. He is not the victim of his trance; he commands it as a bird the air in its flight. The magic of his drum carries him away on the wings of its rhythm, the wings of spiritual transport. While in his trance he is flying as a bird to the upper world, or descending as a reindeer, bull or bear to the world beneath.

The basic form of the shamanistic crisis can be summarized as follows: firstly, a spontaneously precipitated rupture with the world of common day, revealed in symptoms analogous to those of a serious nervous breakdown (visions of dismemberment, fosterage in the world of the spirits, and restitution). Secondly, a course of shamanistic, mythological instruction under a master, through which an actual restitution of a superior level is achieved. Thirdly, a career of magical practice in the service of the community, defended from the natural resentment of the assisted community by various tricks and parodies of power.

The Fire-Bringer.

The figure of the trickster appears to have been the chief mythological character of the world of story. He appeared under many guises, both animal and human. He is the culture-bringer, but also the epitome of the principle of disorder. In the Paleolithic sphere from which this figure derives, he was the archetype of the hero, the giver of all great boons – the fire-bringer and the teacher of mankind. Beyond the ethical dualism of god and devil, the trickster shows the creative force in its primary innocence. The hunting tribes of North America attribute the same shamanistic earth-fashioning deed to their Paleolithic hero-trickster.

Paleolithic mythology and The Animal Master.

Legends of hunting tribes, supported by evidence found in the Paleolithic caves of southern France (dating back to about 30 000 B.C.), give indications of several clues of particular importance to understanding Paleolithic mythology.

Firstly, the action is not placed in an earlier mythological age, but in a world like their present world. Where shamanism is involved, the mythological age and realm are here and now. Secondly, a central figure is a bird (magpie) without whose work as intermediary nothing could have been accomplished. This bird symbolizes the shaman-trickster, whose social function in the tribe was to serve as the intermediary between man and the powers behind the veil of nature. Thirdly, a dead man’s return to life is made possible by the finding of a particle of bone. Fourthly, the game animals when being chased to a fall and actually going over it, are acting under the influence of the animal master. Fifthly, when the animals - under the influence of the animal master – went over the fall, their flesh is to be regarded as the willed gift of that master to the people. Sixthly, there is a right way and a wrong way to kill animals. When the animal rites are properly celebrated by the people, there is a magical accord between the animals and those who have to hunt them. The hunt itself is a rite of sacrifice, and the proper sacrifice is the animal itself, which through its death and return represents a permanent process in the shadow world of accident and chance.