The Separation of East and West

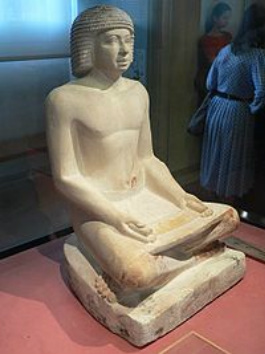

Scribe, Dynasty V, Wikimedia Commons

The Cities of God

The Age of Wonder and Mythogenesis

Two mighty motives run through the mythologies and religions of the world. They are different and have different histories. The first and the earlier to appear may be termed wonder in one or another of its modes, from mere bewilderment in the contemplation of something inexplicable to arrest in daemonic dread or mystic awe. The second is self-salvation: redemption or release from a world exhausted of its glow. When the Buddha extinguished ego in himself, the world burst into flower. That, exactly, is the way it has always appeared to those in whom wonder – and not salvation – is religion.

A galaxy of female figurines that comes to view in the archaeological strata of the nuclear Near East about 4500 B.C. provides our first clue to the focus of the earliest Neolithic farming and pastoral communities. The images are of bone, clay, stone, or ivory. They are standing or seared, usually naked, often pregnant, and sometimes holding or nursing a child. Associated symbols appear on the painted ceramic wares of the same archaeological strata. Among these a prominent motif (for instance in the so-called Halaf ware of the Syro-Cilician corner) is the head of a bull, seen from before, with long, curving horns – suggesting that the widely known myth must already have been developed, of the earth-goddess fertilized by the moon-bull who dies and is resurrected. Familiar derivatives of this myth are the Late Classical legends of Europa and the Bull of Zeus, Pasiphaë and the Bull of Poseidon, Io turned into a cow, and the killing of the Minotaur. Moreover, the earliest temple compounds of the Near East – indeed, the earliest temple compounds in the history of the world – reinforce the evidence for the bull-god and goddess-cow as leading fertility symbols of the period.

Roughly dated, about 4000 – 3500 B.C., three such primary temple compounds have been excavated in the Mesopotamian south, at Obeid, Uruk, and Eridu; two a little north, at Khafajah and Uqair, respectively north and south of Bagdad; while a sixth, far away, at Tell Brak, in the Kabur valley of northeastern Syria, suggests a broad diffusion of the common form from that Syro-Cilician (so-called Taurean) corner. Two of these six compounds are known to have been dedicated to goddesses: that of Obeid to Ninhursag, that of Khafajah to Inanna; the deities of the others being unknown. And three of the compounds (at Obeid, Khafajah, and Uqair), each enclosed by two surrounding high walls, were of an oval form designed, apparently, to suggest the female genitalia. For, like Indian temples of the mother-goddess, where the innermost shrine has a form symbolic of the female organ, so were these symbolic of the generative force of nature by analogy with the bearing and nourishing powers of the female.

Visitors to temples in India have been fed milk-rice or other such dairy-made food, which is ritually dispensed as her “bounty” (prasad). In South India, in the Nilgiri hills, there is an enigmatic tribe, the Todas, unrelated racially to its neighbors, whose little temple compounds are dairies, where they keep cattle that they worship. At their chief sacrifice – which is of a calf, the symbolic son of the mother – they address to their goddess Togorsh a prayer that includes the word Ninkurshag, which they cannot interpret. There can be no doubt that in the royal cattle barns of the goddesses Ninhurshag of Obeid and Inanna of Khafajah, a full millennium and a half before the first signs of any agrarian-pastoral civilization eastward of Iran, we have the prelude to the great ritual symphony of bells, waved lights, prayers, hymns, and lowing sacrificial kine, that has gone up to the goddess in India throughout the ages.

There is an early Sumerian seal of about 3500 B.C. from Uruk. Every one of its elements was related in later art and cult to the mythology of the dead and resurrected god Tammuz (Sumerian Dumuzi), prototype of the Classical Adonis, who was the consort, as well as son by virgin birth, of the goddess-mother of many names: Inanna, Ninhurshag, Ishtar, Astarte, Artemis, Demeter, Aphrodite, Venus. Throughout the ancient world, large mounds of earth in the center of shrines were symbolic of the goddess. It is to be compared to the early Buddhist reliquary mounds (stupas). Magnified, it is the mountain of the gods (Greek Olympos, Indian Meru) with the radiant city of the deities atop, the watery abyss beneath, and the ranges of life between.

Between the period of the earliest female figurines of about 4500 B.C. and that of the Sumerian seals, a span of thousand years elapsed, during which the archaeological signs constantly increase of a cult of the tilled earth fertilized by that noblest and most powerful beast of the recently developed holy barnyard, the bull – who not only sired the milk-yielding cows, but also drew the plow, which in that early period simultaneously broke and seeded the earth. Moreover, by analogy, the horned moon, lord of the rhythm of the womb and of the rains and dews, was equated with the bull; so that the animal became a cosmological symbol, uniting the fields and laws of sky and earth. The whole mystery of being could thus be poetically illustrated through the metaphor of the cow, the bull, and their calf, liturgically rendered within the precincts of the early temple compounds – which were symbolic of the womb of the cosmic goddess Cow herself.

During the following millennium, however, the basic village culture flowered and expanded into a civilization of city states, particularly in lower Mesopotamia. By then, the poetic liturgy of the cosmic sacrifice now was enacted chiefly upon kings, who were periodically slain, sometimes together with their courts. For it was the court, not the dairy, that now represented the latest, most impressive magnification of life. The art of writing had been invented about 3200 B.C. (Uruk); the village was definitively supplanted by the temple-city, and a full-time professional priestly caste had assumed the guidance of the civilization. A mathematically correct calendar was invented to regulate the seasons of the temple-city’s life according to the celestial laws so revealed. The celestial laws were as far as possible literally imitated in the ritual patterns of the court, so that the cosmic and the social order should be one.

Culture Stage and Culture Style

Joseph Campbell considers the root of mythology and religion to be an apprehension of the numinous (i.e. something indicating the presence of a divinity, something spiritual, or awe-inspiring). The symbolism of the temple and atmosphere of myth are, in this sense, catalysts of the numinous – and therein lies the secret of their force. However, the traits of the symbols and elements of the myths tend to acquire a power of their own through association, by which the access of the numinous itself may become blocked. And it does, indeed, become blocked when the images are insisted upon as final terms in themselves: as they are, for example, in a dogmatic credo.

With the radical transfer of focus effected by the turn of mankind from the hunt to agriculture and animal domestication, the older mythological metaphors lost force; and with the recognition – about 3500 B.C. – of a mathematically calculable cosmic order almost imperceptibly indicated by planetary lights, a fresh, direct impact of wonder was experienced, against which there was no defense. The force of the attendant seizure can be judged from the nature of the rites of that time. The appearance in the period 4500 – 2500 B.C. of an unprecedented constellation of sacra – sacred acts and sacred things – points not to a new theory about how to make the beans grow, but to an actual experience in depth of that “mysterium tremendum” that would break upon us all even now, were it not so wonderfully masked.

The system of new arts and ideas brought into being within the precincts of the great Sumerian temple compounds passed to Egypt around 2800 B.C., Crete and the Indus around 2600 B.C., China around 1600 B.C., and America within the following thousand years. However, the religious experience itself around which the new elements of civilization had been constellated was not – and could not be – disseminated. Not the seizure itself, but its liturgy and associated arts, went forth to the winds; and these were applied, then, to alien purposes, adjusted to new geographies, and to very different psychological structures from that of the ritually sacrificed god-kings.

We may take as example the case of the mythologies of Egypt, which for the period of around 2800 – 1800 B.C. are the best documented in the world. The myths of the dead and resurrected god Osiris so closely resemble those of Tammuz, Adonis, and Dionysos as to be practically the same. All were related in the period of their prehistoric development to the rites of the killed and resurrected divine king. The earliest center from which the idea of a state governed by a divine king was diffused, was almost certainly from Mesopotamia.

The Hieratic State

The earliest known work of art exhibiting the characteristic style of Egypt is a carved stone votive tablet discovered at Hierakonpolis in Upper Egypt, which appears to have been the native place of coronation of a line of kings devoted to the solar-falcon Horus. About 2850 B.C. these kings moved north, into Lower Egypt, and established the first dynasty of the two lands. The painting found on the walls at Hierakonpolis showed Mesopotamian origin. All the motifs came to Egypt from the Southwest Asian sphere, where they had appeared as motifs on the painted pottery (Samarra) as early as about 4500 B.C.

And yet, Egyptian art of the Narmer Palette (about 2850 B.C.) reveals suddenly not only an elegance of style and manner of carving stone but also a firmly formulated mythology that are characteristically and unquestionably its own. The monarch depicted is the pharaoh Narmer, whom a number of scholars identify with Menes, the uniter of the two lands of Upper and Lower Egypt, about 2850 B.C.. The deed commemorated on the palette seems to be exactly that of his conquest of the North.

On both sides of the Narmer Palette there appear two heavily horned heads of the cow-goddess Hathor in the top panels, four heads in all. Four is the number of the quarters of the sky, and the goddess, thus pictured four times, was to be conceived as bounding the horizon. In the Egyptian mythology, Hathor stood upon the earth in such a way that her four legs were the pillars of the four quarters. Her belly was the firmament. The sun, the golden solar falcon Horus, flying east to west, entered her mouth each evening to be born again the next dawn. Horus thus was the “bull of his mother”, his own father. And the cosmic goddess, whose name, hat-hor, means “the house of Horus”, was accordingly both the consort and the mother of this self-begetting god (who in one aspect was a bird of prey). In the aspect of the father, the mighty bull, this god was Osiris and identified with the dead father of the living pharaoh. In the aspect of son, the falcon, Horus, he was the living pharaoh now enthroned. Substantially, however, these two, the living pharaoh and the dead, Horus and Osiris, were the same. The pharaonic principle, Pharaoh with a capital P, was an eternal, not mortal, being.

Thus there was an attribution of immortal substance to a sequence of mortal men. In those days this was overlooked by dressing up and regarding the costume, not the man, as in a play, so that the scripture might be fulfilled. Thomas Mann said, in discussing the phenomenon of “lived myth”: “The Ego of antiquity and its consciousness of itself was different from our own, less exclusive, less sharply defined. It was, as it were, open behind; it received much from the past and by repeating it gave it presentness again.” For such an imprecisely differentiated sense of ego, “imitation” meant far more than we mean by the word today. It was a mythical identification. Life, or at any rate significant life, was the reconstitution of the myth in flesh and blood.

Mythic Identification

From a series of tombs unearthed near Abydos in Upper Egypt, one can get an idea of the nature of the funeral rites that were in force in the period of Old Kingdom Egypt (from about 2850 B.C. to about 2190 B.C.). The tomb and necropolis of King Narmer shows numerous subsidiary graves. Later finds have also given clear indications of a pattern of burials with vast human sacrifice – usually the wife, harem and close attendants of the buried kings. This seemed to last until Dynasty V (around 2350 B.C.), when the custom of human sacrifice at royal burials had been abandoned. During the half-millenium between the founding of Dynasty I (about 2850 B.C.) and the fall of Dynasty V, a coming to climax and transformation of the pharaonic cult of the mighty bull took place.

We find numerous analogies between antiquities of Egypt and of India. The figure of the cow is an obvious analogy. Already in the Rig Veda (about 1500 – 1000 B.C.) the goddess Aditi, mother of the gods, was a cow. She was the mother of the sun-god Mitra and of the lord of truth and universal order, Varuna; mother, also, of Indra, king of the gods, who is addressed constantly as a bull and is the archetype of the world monarch. In the later Hinduism of the Tantric and Puranic periods (about 500 – 1500 A.D.), when the rites and mythologies of Vishnu and Shiva came to full flower, Shiva was identified with the bull, Vishnu with the lion. Shiva’s animal vehicle was the white bull Nandi. Shiva’s consort, furtherrmore, the goddess Sati (ref.suttee), who destroyed herself because of her love and loyalty, is the model of the perfect Indian wife. Finally, the Indian mythological figure and ideal of the universal king (cakravartin), the bound of whose domain is the horizon, before whose advance the sun-wheel (cakra) rolls (vartati) as a manifestation of divine authority and as opener of the way to the four quarters. When buried, he is to have huge mound (stupa) erected over his remains. He is, without doubt, a perfect counterpart of the old Egyptian image and ideal of the pharaoh.

As in India to this day, so also in the deep Egyptian past, we find this rite of suttee. And we discover it again in earliest China. The royal tombs of Ur show it in Mesopotamia, and there is evidence in Europe as well. The human beings in these sacrifices were not – especially in its ancient origins - seen as individuals, but as parts of a categorical imperative within a larger mythological picture.

Mythic Inflation

Gradually, around the period of the Narmer Palette, the holy death-and-resurrection scenes were no longer being played with all the empathy of yore – at least by the players in the leading part. At some point on the prehistoric map, the king had taken control of the situation, so that by the time the earliest datable royal actors came striding, the seremony had a new reading. The audience now watched a solemn symbolic mime, the Sed festival, in which the king renewed his pharaonic warrant without submitting to the personal inconvenience of literal death. The real hero of the great occasion was no longer the timeless Pharaoh (capital P), who puts on pharaohs like clothes, and puts them off, but the living garment of flesh and bone (pharaoh So-and-so) who, instead of giving himself to the part, now had found a way to keep the part to himself. Instead of Pharaoh changing pharaohs, it was the pharaoh who changed costumes.

However, during the first five dynasties, even though the pharaohs themselves had by now acquired this new way of leading the rituals, their wives, concubines, harem keepers, palace guards were still left with the hard part when the pharaoh actually died (of other causes). They had to follow the corpse of the pharaoh into the underworld prepared for them by him. By now, the function of the cult was to reunite by magic the corporeal soul (the ba) and the incorporeal energetic principle (the ka) which had slipped away at death. This done, it was supposed, there would be no death. This represented a secondary stage of mythic seizure: not mythic identification (ego absorbed and lost in God), but the opposite, mythic inflation (the god absorbed and lost in ego). The first characterized the actual holiness of the sacrificed kings of the early hieratic city states, and the second, the mock holiness of the worshipped kings of the subsequent dynastic states. The pharaohs in their cult were no longer simply imitating the holy past, “so that the scripture might be fulfilled”. They and their priests were creating something of and for themselves. This was an era of grandiose, highly self-interested, prodigiously inflated egos. This transition indicated a move from: 1. Mythic identification and the hieratic, pre-dynastic state, to: 2. Mythic inflation and the archaic dynastic states.

In the pageantry of the Sed festival, two coronations were celebrated, representing the two antagonists, Horus (the hero) and Seth (the villain). The monarch himself is termed “the appearing of the dual power in which the two gods are at peace”. Mythologically representing the inevitable dialectic of temporality, where all things appear in pairs, Horus and Seth are forever in conflict; whereas in the sphere of eternity, beyond the veil of time and space, where there is no duality, they are at one; death and life are at one; all is peace. And of this peace, which is the inhabiting reality of all things, all history and sorrow, the living god Pharaoh is the pivot. He is an epitome of the field – the universe itself – in which the pairs of opposite play. Hence, to follow him in death is to remain in life, there being in fact no death in the royal pasture beyond time, where the two gods are at one and the shepherd crook gives assurance.

This secret knowledge that there is the peace of eternal being within every aspect of the field of temporal becoming is the signature of this entire civilization. It is the metaphorical background of the majesty of its sculpture as well as the nobility of its pharaonic cult of death. Pharaoh was known as “The Two Lords”.

The Immanent Transcendent God

A text from Memphis in the Old Kingdom anticipated by two thousand years the idea of creation by the power of the Word which appears in the Book of Genesis, where God said, “Let there be light”, and there was light. In the Memphite text of the mummy-god Ptah we are told that it was the heart of God that brought forth every issue and the tongue of God that repeated what the heart had thought: “Every divine word came into existence by the thought of the heart and the commandment of the tongue. When the eyes see, the ears hear, and the nose breathes, they report to the heart. It is the heart that brings forth every issue, and the tongue that repeats the thought of the heart. Thus were fashioned all the gods: even Atum and his Ennead.”

The priestly minds of the temple of Ptah, in the capital city (Memphis) founded by the first pharaoh, display in this text a view of the nature of deity (in about 2850 B.C.) that is at once psychological and metaphysical. The organs of the human body are associated with psychological functions: the heart with creative conception; the tongue with creative realization. Thus the Memphite priesthood of the creator-deity Ptah deepened the meaning and force of their god’s name when they penetrated psychologically to a new depth in their understanding of the nature of creativity itself. By this feat they went past the neighboring priesthood of the ancient city of On (Heliopolis), whose concept of creation had been rendered in the myth of their own local creator-deity, the sun-god Atum.

We have two accounts of the creative acts of Atum, both from the Pyramid Texts – which are the earliest known body of religious writings preserved anywhere in the world, inscribed on a series of nine tombs (about 2350 – 2175 B.C.) in the cast necropolis of Memphis, at Sakkara. According to the first of these accounts: “Atum created in Heliopolis by an act of masturbation. He took his phallus in his fist, to excite desire thereby. And the twins were born, Shu and Tefnut.” According to the second version, creation was from the spittle of his mouth, the god standing at the time on the summit of the cosmic maternal mound, symbolized as a pyramid: “O Atum-Khepri, when thou didst mount the hill, And didst shine like the phoenix on the ancient pyramidal stone in the Temple of the Phoenix in Heliopolis, Thou didst spit out what was Shu, sputter out what was Tefnut. And thou didst put thine arms about them as the arms of a ka, that thy ka might be in them.” Atum, therefore, like the Self in the Indian Upanishad, poured himself physically into creation. There is no developed psychological analogy indicated in either of these two Egyptian texts – which are certainly much older than the inscriptions in which they are preserved. They present a primary image of physical creation.

The twins Shu and Tefnut were male and female, and it was from them that the rest of the pantheon derived. The gods begotten from them were the heaven-goddess Nut and her spouse, the earth-god Geb, who in turn begot two divine sets of opposed twins, Isis and Osiris, Nephtys and her brother-consort Seth. So, already in the priestly system of the temple of the sun-god of Heliopolis, a mythology had been developed wherein nine gods (known as the Ennead of Heliopolis) were brought together in a hierarchic order.

Compare now the Memphite insight by which this primary theology was surpassed: “There came into being on the heart and tongue of Ptah, something in the image of Atum.” (The rival creator in a physical sense here is shown as the mere agent of an antecedent spiritual force.) “Mighty and great is Ptah, who rendered power to the gods and their kas: through his heart, by which Horus became Ptah; and through his tongue, by which Thot became Ptah.” (Thot was an ancient moon-god of the city of Hermopolis, who had been brought into the syncretic system of Heliopolis in the role of scribe, messenger, master of the word and the magic of the resurrection. In the great hall in which the dead are judged he records the weights of their hearts. His animal forms are the ibis and the baboon. As an ibis he sails over the sky. As a baboon, he greets the rising sun.)

As symbolic of the creative word, Thot is in the Memphite system identified with the power of the tongue of Ptah. Likewise, the solar power that Thot greets in its rising, namely Horus, the living son and resurrection of the creative power of Osiris, here is identified with the power of the heart of Ptah. The gods are thus functioning members of the larger body, or totality, of Ptah, who dwells in them as their eternal vital force, their ka: “Thus the heart and tongue won mastery over all the members, in as much as he is in every body and every mouth of all gods, all men, all beasts, all crawling things, and whatever lives, since he thinks and commands everything as he wills.” The idea is here announced unmistakenly of the immanent God that is yet transcendent, which lives in all gods, all men, all beasts, all crawling things, and whatever lives. The whole pantheon, as well as the world, thus becomes organically assimilated to the cosmic body of the creator. The Indian image of the Self that became creation is thus anticipated by a full two thousand years.

The myths cannot therefore be taken simply in their literal sense. They have to be understood as a rendition of deeper thoughts, striving to comprehend the world spiritually, as a unit. The god Ptah was said to be incarnate in a black bull miraculously engendered by a moonbeam. This bull, the Apis bull, when ceremonially slain upon attaining the age of twenty-five, was embalmed and buried in the necropolis of Sakkara in a rock cut tomb known as the Serapeum. Immediately, a new incarnation of the god was born. The metaphor of the sacrificed bull must have been felt to be an adequate substitute for that of the sacrificed king. In the pre-dynastic age, the moon-king had been ritually slain, but in this later age it was the bull – so that the king, relieved of numinous weight, was released for his political ballet.

Ptah is depicted as a mummy; and the Apis bull is black. Both the mummy and the blackness of the bull refer to the dark moon, the dead moon, into which the old moon dies and from which the new is born. Analogously, the mythology of the death of Osiris and birth of Horus is no more than a manifestation in time of a deeper, timeless Ptah. In India, in the late tantric imagery of the period 500 – 1500 A.D., there are several interesting analogies to be pointed out. Shiva in one aspect appears in the form of a corpse, known as Shava. The animal of Shiva is the bull Nandi. Both symbolic systems refer to the god as transcendent and simultaneously immanent. The animal vehicle of the goddess consort of Shiva is the lion, whereas the goddess consort of Ptah is the lion-goddess Sekhmet.

In the early mythologies of the moon-bull, the sun was always conceived as a warlike, blazing, destructive deity. In the heat of the tropics it is indeed a terrible force, whereas the moon, dispenser of the night dews represents the principle of life: the principle of birth and death that is life. The solar bird or lioness is only an agent of a principle of death that inheres already in the nature of life itself. The sun is a manifestation of only one aspect of the life/death principle, which is more fully symbolized in the moon: in the moon-bull attacked by the lion. Ptah’s son by Sekhmet is the ruling pharaoh – symbolized in the human-headed, lion-bodied Sphinx, among the pyramids wherein the Osiris-bodies of the pharaohs silently reside. The Uraeus Serpent of pharaonic authority appears from the mid-point of the brow of the Sphinx. Analogously, in the Shivaite symbolism of India this is the point of the third eye, known as the center of command (ajna), wherefrom the annihilating blaze of the so-called Serpent Power of the god flashes in his wrath.

The Priestcraft of Art

The period of Khasekhemui, at the close of the reign of Dynasty II (about 2650 B.C.), was one of sudden advance in all the arts. The potter’s wheel had recently been introduced (which in Southwest Asia had appeared as early as about 4000 B.C.), copper was coming abundantly into use, a new corpus of stone vessels made an appearance, and the art of carving stone, both in relief and in the round, began to move toward mastership. With Dynasty II (about 2650 – 2600 B.C.), there came a decisive shift of political emphasis north to Memphis, the grim series of suttee tombs at Abydos terminated, and in the Memphite necropolis at Sakkara there appeared, about 2630 B.C., the fabulous Step Pyramid of the pharaoh Zoser. It was in white limestone, and the burial chamber was cut far down into the limestone beneath, into which immense blocks of hardest granite were lowered for the construction of the mausoleum.

Among the fragments found in excavations in the Twentieth Century, was a monolithic base of a throne, ornamented by fourteen lion (not bull) heads, carved in round form. An age had passed: that of the bull. Another had dawned: that of the lion. The mythology of the lunar bull was henceforth to be overlaid, and not alone in Egypt, by a solar mythology of the lion. The lunar light waxes and wanes. That of the sun is forever bright. The moon is the lord of growth, the waters, the womb, and the mysteries of time; the sun, of the brilliance of the intellect, sheer light, and eternal laws that never change. The priesthood now known to have been responsible for Egypt’s art and architecture in stone was that of the temple compound of Ptah. Led by a high priest who held the title “master of the master craftsmen”, this may be seen as the greatest art school of the ancient world until the brief period of Athens in its prime. It is entirely to them that the world owes the ruins not only of the Step Pyramid of Dynasty III, but also of the Pyramid Age of Dynasties IV – VI (about 2600 – 2190 B.C.), and therewith the earliest manifestation in firmly datable stone of practically all of the basic rules, techniques and formulae upon which the arts of architecture and sculpture in stone have been grounded ever since.

Mythic Subordination

The magnitude of the Cheops Pyramid illustrates the proportions to which an untrammeled ego may grow under unchecked conditions. However, at the high period of the Pyramid Age itself, a new, comparatively humane, benevolent, fatherly quality began to be apparent in the character and behavior of the pharaohs of Dynasty IV. Having seen (through the inscriptions on the tombs) the extent of megalomania and cruelty practiced before Dynasty IV, one can only wonder what the sobering influences might have been by which those monsters of the great big “I” were rendered human and humane.

A breakthrough for Egypt came with the fall of Dynasty IV and appearance of the priest-founded Dynasty V (2480 – 2350 B.C.). At that moment, and from that moment onward, the pharaoh, though still a god, was to know and comport himself as a god not of first rank but of second rank. A new myth sprang to the fore: of a new and glorious divinity, the sun-god named Re, who was not, like Horus, the sun, but himself father of the pharaoh, as well as of all else. He was identified with Atum, but has a different quality and force. There is a legend of the virgin birth of the first three pharaohs of the reign, where they are represented as sons of the god Re. This may be assumed to be the origin myth of the dynasty itself. Its sunny atmosphere of play is characteristic of the mythic mood of solar as opposed to lunar thought. A fresh breath of clean air has come blowing into the field.

We take note of the virgin-birth motif. In the earlier mythology the pharaoh had been the bull of his mother; he is not to be so any more. An eternal, higher principle of pure light has been turned against the earlier, fluctuating principle of both darkness and light, death and resurrection, as the sun against the moon. The sun never dies. The sun descends into the netherworld, battles the demons of the night sea, is in danger, but never dies. Campbell presents a record of a sequence of psychological transformations, as follows.

1.From an antecedent pre-dynastic stage of mythic identification, characterized by the submission of all human judgment to the wonder of a supposed cosmic order, announced by a priesthood, and executed upon a sacrificed god-king.

2.Through an early dynastic stage of mythic inflation (Dynasties I – IV, about 2850 – 2480 B.C.), when the will of the god-king himself became the signal of destiny and a vastly creative, daemoniac pathology conjured into being a symbolic civilization.

3.To a culminating stage of mythic subordination (Dynasty V, about 2480 – 2350 B.C. and thereafter), where the king, though still in his mythic role, no longer played the untrammeled part of a “mysterium tremendum” made flesh, but brought to bear against himself the censorship of an order of human judgment.

Thus, in the way of a communal psychoanalytic cure, the civilization was brought, through the person of its symbolic king, from a state of fascinated cosmic seizure to one of reasonably balanced humanity. Human values projected upon the universe – goodness, benevolence, mercy, and the rest – were attributed to its creator, and the taming of the pharaoh was achieved as a reflection of this supposed humanity of the universal god. The inhabiting spirit of the mythology is wonder, not guilt, and in this sense Egyptian mythology belongs more to the context of Oriental than to Western mythology.

Two mighty motives run through the mythologies and religions of the world. They are different and have different histories. The first and the earlier to appear may be termed wonder in one or another of its modes, from mere bewilderment in the contemplation of something inexplicable to arrest in daemonic dread or mystic awe. The second is self-salvation: redemption or release from a world exhausted of its glow. When the Buddha extinguished ego in himself, the world burst into flower. That, exactly, is the way it has always appeared to those in whom wonder – and not salvation – is religion.

A galaxy of female figurines that comes to view in the archaeological strata of the nuclear Near East about 4500 B.C. provides our first clue to the focus of the earliest Neolithic farming and pastoral communities. The images are of bone, clay, stone, or ivory. They are standing or seared, usually naked, often pregnant, and sometimes holding or nursing a child. Associated symbols appear on the painted ceramic wares of the same archaeological strata. Among these a prominent motif (for instance in the so-called Halaf ware of the Syro-Cilician corner) is the head of a bull, seen from before, with long, curving horns – suggesting that the widely known myth must already have been developed, of the earth-goddess fertilized by the moon-bull who dies and is resurrected. Familiar derivatives of this myth are the Late Classical legends of Europa and the Bull of Zeus, Pasiphaë and the Bull of Poseidon, Io turned into a cow, and the killing of the Minotaur. Moreover, the earliest temple compounds of the Near East – indeed, the earliest temple compounds in the history of the world – reinforce the evidence for the bull-god and goddess-cow as leading fertility symbols of the period.

Roughly dated, about 4000 – 3500 B.C., three such primary temple compounds have been excavated in the Mesopotamian south, at Obeid, Uruk, and Eridu; two a little north, at Khafajah and Uqair, respectively north and south of Bagdad; while a sixth, far away, at Tell Brak, in the Kabur valley of northeastern Syria, suggests a broad diffusion of the common form from that Syro-Cilician (so-called Taurean) corner. Two of these six compounds are known to have been dedicated to goddesses: that of Obeid to Ninhursag, that of Khafajah to Inanna; the deities of the others being unknown. And three of the compounds (at Obeid, Khafajah, and Uqair), each enclosed by two surrounding high walls, were of an oval form designed, apparently, to suggest the female genitalia. For, like Indian temples of the mother-goddess, where the innermost shrine has a form symbolic of the female organ, so were these symbolic of the generative force of nature by analogy with the bearing and nourishing powers of the female.

Visitors to temples in India have been fed milk-rice or other such dairy-made food, which is ritually dispensed as her “bounty” (prasad). In South India, in the Nilgiri hills, there is an enigmatic tribe, the Todas, unrelated racially to its neighbors, whose little temple compounds are dairies, where they keep cattle that they worship. At their chief sacrifice – which is of a calf, the symbolic son of the mother – they address to their goddess Togorsh a prayer that includes the word Ninkurshag, which they cannot interpret. There can be no doubt that in the royal cattle barns of the goddesses Ninhurshag of Obeid and Inanna of Khafajah, a full millennium and a half before the first signs of any agrarian-pastoral civilization eastward of Iran, we have the prelude to the great ritual symphony of bells, waved lights, prayers, hymns, and lowing sacrificial kine, that has gone up to the goddess in India throughout the ages.

There is an early Sumerian seal of about 3500 B.C. from Uruk. Every one of its elements was related in later art and cult to the mythology of the dead and resurrected god Tammuz (Sumerian Dumuzi), prototype of the Classical Adonis, who was the consort, as well as son by virgin birth, of the goddess-mother of many names: Inanna, Ninhurshag, Ishtar, Astarte, Artemis, Demeter, Aphrodite, Venus. Throughout the ancient world, large mounds of earth in the center of shrines were symbolic of the goddess. It is to be compared to the early Buddhist reliquary mounds (stupas). Magnified, it is the mountain of the gods (Greek Olympos, Indian Meru) with the radiant city of the deities atop, the watery abyss beneath, and the ranges of life between.

Between the period of the earliest female figurines of about 4500 B.C. and that of the Sumerian seals, a span of thousand years elapsed, during which the archaeological signs constantly increase of a cult of the tilled earth fertilized by that noblest and most powerful beast of the recently developed holy barnyard, the bull – who not only sired the milk-yielding cows, but also drew the plow, which in that early period simultaneously broke and seeded the earth. Moreover, by analogy, the horned moon, lord of the rhythm of the womb and of the rains and dews, was equated with the bull; so that the animal became a cosmological symbol, uniting the fields and laws of sky and earth. The whole mystery of being could thus be poetically illustrated through the metaphor of the cow, the bull, and their calf, liturgically rendered within the precincts of the early temple compounds – which were symbolic of the womb of the cosmic goddess Cow herself.

During the following millennium, however, the basic village culture flowered and expanded into a civilization of city states, particularly in lower Mesopotamia. By then, the poetic liturgy of the cosmic sacrifice now was enacted chiefly upon kings, who were periodically slain, sometimes together with their courts. For it was the court, not the dairy, that now represented the latest, most impressive magnification of life. The art of writing had been invented about 3200 B.C. (Uruk); the village was definitively supplanted by the temple-city, and a full-time professional priestly caste had assumed the guidance of the civilization. A mathematically correct calendar was invented to regulate the seasons of the temple-city’s life according to the celestial laws so revealed. The celestial laws were as far as possible literally imitated in the ritual patterns of the court, so that the cosmic and the social order should be one.

Culture Stage and Culture Style

Joseph Campbell considers the root of mythology and religion to be an apprehension of the numinous (i.e. something indicating the presence of a divinity, something spiritual, or awe-inspiring). The symbolism of the temple and atmosphere of myth are, in this sense, catalysts of the numinous – and therein lies the secret of their force. However, the traits of the symbols and elements of the myths tend to acquire a power of their own through association, by which the access of the numinous itself may become blocked. And it does, indeed, become blocked when the images are insisted upon as final terms in themselves: as they are, for example, in a dogmatic credo.

With the radical transfer of focus effected by the turn of mankind from the hunt to agriculture and animal domestication, the older mythological metaphors lost force; and with the recognition – about 3500 B.C. – of a mathematically calculable cosmic order almost imperceptibly indicated by planetary lights, a fresh, direct impact of wonder was experienced, against which there was no defense. The force of the attendant seizure can be judged from the nature of the rites of that time. The appearance in the period 4500 – 2500 B.C. of an unprecedented constellation of sacra – sacred acts and sacred things – points not to a new theory about how to make the beans grow, but to an actual experience in depth of that “mysterium tremendum” that would break upon us all even now, were it not so wonderfully masked.

The system of new arts and ideas brought into being within the precincts of the great Sumerian temple compounds passed to Egypt around 2800 B.C., Crete and the Indus around 2600 B.C., China around 1600 B.C., and America within the following thousand years. However, the religious experience itself around which the new elements of civilization had been constellated was not – and could not be – disseminated. Not the seizure itself, but its liturgy and associated arts, went forth to the winds; and these were applied, then, to alien purposes, adjusted to new geographies, and to very different psychological structures from that of the ritually sacrificed god-kings.

We may take as example the case of the mythologies of Egypt, which for the period of around 2800 – 1800 B.C. are the best documented in the world. The myths of the dead and resurrected god Osiris so closely resemble those of Tammuz, Adonis, and Dionysos as to be practically the same. All were related in the period of their prehistoric development to the rites of the killed and resurrected divine king. The earliest center from which the idea of a state governed by a divine king was diffused, was almost certainly from Mesopotamia.

The Hieratic State

The earliest known work of art exhibiting the characteristic style of Egypt is a carved stone votive tablet discovered at Hierakonpolis in Upper Egypt, which appears to have been the native place of coronation of a line of kings devoted to the solar-falcon Horus. About 2850 B.C. these kings moved north, into Lower Egypt, and established the first dynasty of the two lands. The painting found on the walls at Hierakonpolis showed Mesopotamian origin. All the motifs came to Egypt from the Southwest Asian sphere, where they had appeared as motifs on the painted pottery (Samarra) as early as about 4500 B.C.

And yet, Egyptian art of the Narmer Palette (about 2850 B.C.) reveals suddenly not only an elegance of style and manner of carving stone but also a firmly formulated mythology that are characteristically and unquestionably its own. The monarch depicted is the pharaoh Narmer, whom a number of scholars identify with Menes, the uniter of the two lands of Upper and Lower Egypt, about 2850 B.C.. The deed commemorated on the palette seems to be exactly that of his conquest of the North.

On both sides of the Narmer Palette there appear two heavily horned heads of the cow-goddess Hathor in the top panels, four heads in all. Four is the number of the quarters of the sky, and the goddess, thus pictured four times, was to be conceived as bounding the horizon. In the Egyptian mythology, Hathor stood upon the earth in such a way that her four legs were the pillars of the four quarters. Her belly was the firmament. The sun, the golden solar falcon Horus, flying east to west, entered her mouth each evening to be born again the next dawn. Horus thus was the “bull of his mother”, his own father. And the cosmic goddess, whose name, hat-hor, means “the house of Horus”, was accordingly both the consort and the mother of this self-begetting god (who in one aspect was a bird of prey). In the aspect of the father, the mighty bull, this god was Osiris and identified with the dead father of the living pharaoh. In the aspect of son, the falcon, Horus, he was the living pharaoh now enthroned. Substantially, however, these two, the living pharaoh and the dead, Horus and Osiris, were the same. The pharaonic principle, Pharaoh with a capital P, was an eternal, not mortal, being.

Thus there was an attribution of immortal substance to a sequence of mortal men. In those days this was overlooked by dressing up and regarding the costume, not the man, as in a play, so that the scripture might be fulfilled. Thomas Mann said, in discussing the phenomenon of “lived myth”: “The Ego of antiquity and its consciousness of itself was different from our own, less exclusive, less sharply defined. It was, as it were, open behind; it received much from the past and by repeating it gave it presentness again.” For such an imprecisely differentiated sense of ego, “imitation” meant far more than we mean by the word today. It was a mythical identification. Life, or at any rate significant life, was the reconstitution of the myth in flesh and blood.

Mythic Identification

From a series of tombs unearthed near Abydos in Upper Egypt, one can get an idea of the nature of the funeral rites that were in force in the period of Old Kingdom Egypt (from about 2850 B.C. to about 2190 B.C.). The tomb and necropolis of King Narmer shows numerous subsidiary graves. Later finds have also given clear indications of a pattern of burials with vast human sacrifice – usually the wife, harem and close attendants of the buried kings. This seemed to last until Dynasty V (around 2350 B.C.), when the custom of human sacrifice at royal burials had been abandoned. During the half-millenium between the founding of Dynasty I (about 2850 B.C.) and the fall of Dynasty V, a coming to climax and transformation of the pharaonic cult of the mighty bull took place.

We find numerous analogies between antiquities of Egypt and of India. The figure of the cow is an obvious analogy. Already in the Rig Veda (about 1500 – 1000 B.C.) the goddess Aditi, mother of the gods, was a cow. She was the mother of the sun-god Mitra and of the lord of truth and universal order, Varuna; mother, also, of Indra, king of the gods, who is addressed constantly as a bull and is the archetype of the world monarch. In the later Hinduism of the Tantric and Puranic periods (about 500 – 1500 A.D.), when the rites and mythologies of Vishnu and Shiva came to full flower, Shiva was identified with the bull, Vishnu with the lion. Shiva’s animal vehicle was the white bull Nandi. Shiva’s consort, furtherrmore, the goddess Sati (ref.suttee), who destroyed herself because of her love and loyalty, is the model of the perfect Indian wife. Finally, the Indian mythological figure and ideal of the universal king (cakravartin), the bound of whose domain is the horizon, before whose advance the sun-wheel (cakra) rolls (vartati) as a manifestation of divine authority and as opener of the way to the four quarters. When buried, he is to have huge mound (stupa) erected over his remains. He is, without doubt, a perfect counterpart of the old Egyptian image and ideal of the pharaoh.

As in India to this day, so also in the deep Egyptian past, we find this rite of suttee. And we discover it again in earliest China. The royal tombs of Ur show it in Mesopotamia, and there is evidence in Europe as well. The human beings in these sacrifices were not – especially in its ancient origins - seen as individuals, but as parts of a categorical imperative within a larger mythological picture.

Mythic Inflation

Gradually, around the period of the Narmer Palette, the holy death-and-resurrection scenes were no longer being played with all the empathy of yore – at least by the players in the leading part. At some point on the prehistoric map, the king had taken control of the situation, so that by the time the earliest datable royal actors came striding, the seremony had a new reading. The audience now watched a solemn symbolic mime, the Sed festival, in which the king renewed his pharaonic warrant without submitting to the personal inconvenience of literal death. The real hero of the great occasion was no longer the timeless Pharaoh (capital P), who puts on pharaohs like clothes, and puts them off, but the living garment of flesh and bone (pharaoh So-and-so) who, instead of giving himself to the part, now had found a way to keep the part to himself. Instead of Pharaoh changing pharaohs, it was the pharaoh who changed costumes.

However, during the first five dynasties, even though the pharaohs themselves had by now acquired this new way of leading the rituals, their wives, concubines, harem keepers, palace guards were still left with the hard part when the pharaoh actually died (of other causes). They had to follow the corpse of the pharaoh into the underworld prepared for them by him. By now, the function of the cult was to reunite by magic the corporeal soul (the ba) and the incorporeal energetic principle (the ka) which had slipped away at death. This done, it was supposed, there would be no death. This represented a secondary stage of mythic seizure: not mythic identification (ego absorbed and lost in God), but the opposite, mythic inflation (the god absorbed and lost in ego). The first characterized the actual holiness of the sacrificed kings of the early hieratic city states, and the second, the mock holiness of the worshipped kings of the subsequent dynastic states. The pharaohs in their cult were no longer simply imitating the holy past, “so that the scripture might be fulfilled”. They and their priests were creating something of and for themselves. This was an era of grandiose, highly self-interested, prodigiously inflated egos. This transition indicated a move from: 1. Mythic identification and the hieratic, pre-dynastic state, to: 2. Mythic inflation and the archaic dynastic states.

In the pageantry of the Sed festival, two coronations were celebrated, representing the two antagonists, Horus (the hero) and Seth (the villain). The monarch himself is termed “the appearing of the dual power in which the two gods are at peace”. Mythologically representing the inevitable dialectic of temporality, where all things appear in pairs, Horus and Seth are forever in conflict; whereas in the sphere of eternity, beyond the veil of time and space, where there is no duality, they are at one; death and life are at one; all is peace. And of this peace, which is the inhabiting reality of all things, all history and sorrow, the living god Pharaoh is the pivot. He is an epitome of the field – the universe itself – in which the pairs of opposite play. Hence, to follow him in death is to remain in life, there being in fact no death in the royal pasture beyond time, where the two gods are at one and the shepherd crook gives assurance.

This secret knowledge that there is the peace of eternal being within every aspect of the field of temporal becoming is the signature of this entire civilization. It is the metaphorical background of the majesty of its sculpture as well as the nobility of its pharaonic cult of death. Pharaoh was known as “The Two Lords”.

The Immanent Transcendent God

A text from Memphis in the Old Kingdom anticipated by two thousand years the idea of creation by the power of the Word which appears in the Book of Genesis, where God said, “Let there be light”, and there was light. In the Memphite text of the mummy-god Ptah we are told that it was the heart of God that brought forth every issue and the tongue of God that repeated what the heart had thought: “Every divine word came into existence by the thought of the heart and the commandment of the tongue. When the eyes see, the ears hear, and the nose breathes, they report to the heart. It is the heart that brings forth every issue, and the tongue that repeats the thought of the heart. Thus were fashioned all the gods: even Atum and his Ennead.”

The priestly minds of the temple of Ptah, in the capital city (Memphis) founded by the first pharaoh, display in this text a view of the nature of deity (in about 2850 B.C.) that is at once psychological and metaphysical. The organs of the human body are associated with psychological functions: the heart with creative conception; the tongue with creative realization. Thus the Memphite priesthood of the creator-deity Ptah deepened the meaning and force of their god’s name when they penetrated psychologically to a new depth in their understanding of the nature of creativity itself. By this feat they went past the neighboring priesthood of the ancient city of On (Heliopolis), whose concept of creation had been rendered in the myth of their own local creator-deity, the sun-god Atum.

We have two accounts of the creative acts of Atum, both from the Pyramid Texts – which are the earliest known body of religious writings preserved anywhere in the world, inscribed on a series of nine tombs (about 2350 – 2175 B.C.) in the cast necropolis of Memphis, at Sakkara. According to the first of these accounts: “Atum created in Heliopolis by an act of masturbation. He took his phallus in his fist, to excite desire thereby. And the twins were born, Shu and Tefnut.” According to the second version, creation was from the spittle of his mouth, the god standing at the time on the summit of the cosmic maternal mound, symbolized as a pyramid: “O Atum-Khepri, when thou didst mount the hill, And didst shine like the phoenix on the ancient pyramidal stone in the Temple of the Phoenix in Heliopolis, Thou didst spit out what was Shu, sputter out what was Tefnut. And thou didst put thine arms about them as the arms of a ka, that thy ka might be in them.” Atum, therefore, like the Self in the Indian Upanishad, poured himself physically into creation. There is no developed psychological analogy indicated in either of these two Egyptian texts – which are certainly much older than the inscriptions in which they are preserved. They present a primary image of physical creation.

The twins Shu and Tefnut were male and female, and it was from them that the rest of the pantheon derived. The gods begotten from them were the heaven-goddess Nut and her spouse, the earth-god Geb, who in turn begot two divine sets of opposed twins, Isis and Osiris, Nephtys and her brother-consort Seth. So, already in the priestly system of the temple of the sun-god of Heliopolis, a mythology had been developed wherein nine gods (known as the Ennead of Heliopolis) were brought together in a hierarchic order.

Compare now the Memphite insight by which this primary theology was surpassed: “There came into being on the heart and tongue of Ptah, something in the image of Atum.” (The rival creator in a physical sense here is shown as the mere agent of an antecedent spiritual force.) “Mighty and great is Ptah, who rendered power to the gods and their kas: through his heart, by which Horus became Ptah; and through his tongue, by which Thot became Ptah.” (Thot was an ancient moon-god of the city of Hermopolis, who had been brought into the syncretic system of Heliopolis in the role of scribe, messenger, master of the word and the magic of the resurrection. In the great hall in which the dead are judged he records the weights of their hearts. His animal forms are the ibis and the baboon. As an ibis he sails over the sky. As a baboon, he greets the rising sun.)

As symbolic of the creative word, Thot is in the Memphite system identified with the power of the tongue of Ptah. Likewise, the solar power that Thot greets in its rising, namely Horus, the living son and resurrection of the creative power of Osiris, here is identified with the power of the heart of Ptah. The gods are thus functioning members of the larger body, or totality, of Ptah, who dwells in them as their eternal vital force, their ka: “Thus the heart and tongue won mastery over all the members, in as much as he is in every body and every mouth of all gods, all men, all beasts, all crawling things, and whatever lives, since he thinks and commands everything as he wills.” The idea is here announced unmistakenly of the immanent God that is yet transcendent, which lives in all gods, all men, all beasts, all crawling things, and whatever lives. The whole pantheon, as well as the world, thus becomes organically assimilated to the cosmic body of the creator. The Indian image of the Self that became creation is thus anticipated by a full two thousand years.

The myths cannot therefore be taken simply in their literal sense. They have to be understood as a rendition of deeper thoughts, striving to comprehend the world spiritually, as a unit. The god Ptah was said to be incarnate in a black bull miraculously engendered by a moonbeam. This bull, the Apis bull, when ceremonially slain upon attaining the age of twenty-five, was embalmed and buried in the necropolis of Sakkara in a rock cut tomb known as the Serapeum. Immediately, a new incarnation of the god was born. The metaphor of the sacrificed bull must have been felt to be an adequate substitute for that of the sacrificed king. In the pre-dynastic age, the moon-king had been ritually slain, but in this later age it was the bull – so that the king, relieved of numinous weight, was released for his political ballet.

Ptah is depicted as a mummy; and the Apis bull is black. Both the mummy and the blackness of the bull refer to the dark moon, the dead moon, into which the old moon dies and from which the new is born. Analogously, the mythology of the death of Osiris and birth of Horus is no more than a manifestation in time of a deeper, timeless Ptah. In India, in the late tantric imagery of the period 500 – 1500 A.D., there are several interesting analogies to be pointed out. Shiva in one aspect appears in the form of a corpse, known as Shava. The animal of Shiva is the bull Nandi. Both symbolic systems refer to the god as transcendent and simultaneously immanent. The animal vehicle of the goddess consort of Shiva is the lion, whereas the goddess consort of Ptah is the lion-goddess Sekhmet.

In the early mythologies of the moon-bull, the sun was always conceived as a warlike, blazing, destructive deity. In the heat of the tropics it is indeed a terrible force, whereas the moon, dispenser of the night dews represents the principle of life: the principle of birth and death that is life. The solar bird or lioness is only an agent of a principle of death that inheres already in the nature of life itself. The sun is a manifestation of only one aspect of the life/death principle, which is more fully symbolized in the moon: in the moon-bull attacked by the lion. Ptah’s son by Sekhmet is the ruling pharaoh – symbolized in the human-headed, lion-bodied Sphinx, among the pyramids wherein the Osiris-bodies of the pharaohs silently reside. The Uraeus Serpent of pharaonic authority appears from the mid-point of the brow of the Sphinx. Analogously, in the Shivaite symbolism of India this is the point of the third eye, known as the center of command (ajna), wherefrom the annihilating blaze of the so-called Serpent Power of the god flashes in his wrath.

The Priestcraft of Art

The period of Khasekhemui, at the close of the reign of Dynasty II (about 2650 B.C.), was one of sudden advance in all the arts. The potter’s wheel had recently been introduced (which in Southwest Asia had appeared as early as about 4000 B.C.), copper was coming abundantly into use, a new corpus of stone vessels made an appearance, and the art of carving stone, both in relief and in the round, began to move toward mastership. With Dynasty II (about 2650 – 2600 B.C.), there came a decisive shift of political emphasis north to Memphis, the grim series of suttee tombs at Abydos terminated, and in the Memphite necropolis at Sakkara there appeared, about 2630 B.C., the fabulous Step Pyramid of the pharaoh Zoser. It was in white limestone, and the burial chamber was cut far down into the limestone beneath, into which immense blocks of hardest granite were lowered for the construction of the mausoleum.

Among the fragments found in excavations in the Twentieth Century, was a monolithic base of a throne, ornamented by fourteen lion (not bull) heads, carved in round form. An age had passed: that of the bull. Another had dawned: that of the lion. The mythology of the lunar bull was henceforth to be overlaid, and not alone in Egypt, by a solar mythology of the lion. The lunar light waxes and wanes. That of the sun is forever bright. The moon is the lord of growth, the waters, the womb, and the mysteries of time; the sun, of the brilliance of the intellect, sheer light, and eternal laws that never change. The priesthood now known to have been responsible for Egypt’s art and architecture in stone was that of the temple compound of Ptah. Led by a high priest who held the title “master of the master craftsmen”, this may be seen as the greatest art school of the ancient world until the brief period of Athens in its prime. It is entirely to them that the world owes the ruins not only of the Step Pyramid of Dynasty III, but also of the Pyramid Age of Dynasties IV – VI (about 2600 – 2190 B.C.), and therewith the earliest manifestation in firmly datable stone of practically all of the basic rules, techniques and formulae upon which the arts of architecture and sculpture in stone have been grounded ever since.

Mythic Subordination

The magnitude of the Cheops Pyramid illustrates the proportions to which an untrammeled ego may grow under unchecked conditions. However, at the high period of the Pyramid Age itself, a new, comparatively humane, benevolent, fatherly quality began to be apparent in the character and behavior of the pharaohs of Dynasty IV. Having seen (through the inscriptions on the tombs) the extent of megalomania and cruelty practiced before Dynasty IV, one can only wonder what the sobering influences might have been by which those monsters of the great big “I” were rendered human and humane.

A breakthrough for Egypt came with the fall of Dynasty IV and appearance of the priest-founded Dynasty V (2480 – 2350 B.C.). At that moment, and from that moment onward, the pharaoh, though still a god, was to know and comport himself as a god not of first rank but of second rank. A new myth sprang to the fore: of a new and glorious divinity, the sun-god named Re, who was not, like Horus, the sun, but himself father of the pharaoh, as well as of all else. He was identified with Atum, but has a different quality and force. There is a legend of the virgin birth of the first three pharaohs of the reign, where they are represented as sons of the god Re. This may be assumed to be the origin myth of the dynasty itself. Its sunny atmosphere of play is characteristic of the mythic mood of solar as opposed to lunar thought. A fresh breath of clean air has come blowing into the field.

We take note of the virgin-birth motif. In the earlier mythology the pharaoh had been the bull of his mother; he is not to be so any more. An eternal, higher principle of pure light has been turned against the earlier, fluctuating principle of both darkness and light, death and resurrection, as the sun against the moon. The sun never dies. The sun descends into the netherworld, battles the demons of the night sea, is in danger, but never dies. Campbell presents a record of a sequence of psychological transformations, as follows.

1.From an antecedent pre-dynastic stage of mythic identification, characterized by the submission of all human judgment to the wonder of a supposed cosmic order, announced by a priesthood, and executed upon a sacrificed god-king.

2.Through an early dynastic stage of mythic inflation (Dynasties I – IV, about 2850 – 2480 B.C.), when the will of the god-king himself became the signal of destiny and a vastly creative, daemoniac pathology conjured into being a symbolic civilization.

3.To a culminating stage of mythic subordination (Dynasty V, about 2480 – 2350 B.C. and thereafter), where the king, though still in his mythic role, no longer played the untrammeled part of a “mysterium tremendum” made flesh, but brought to bear against himself the censorship of an order of human judgment.

Thus, in the way of a communal psychoanalytic cure, the civilization was brought, through the person of its symbolic king, from a state of fascinated cosmic seizure to one of reasonably balanced humanity. Human values projected upon the universe – goodness, benevolence, mercy, and the rest – were attributed to its creator, and the taming of the pharaoh was achieved as a reflection of this supposed humanity of the universal god. The inhabiting spirit of the mythology is wonder, not guilt, and in this sense Egyptian mythology belongs more to the context of Oriental than to Western mythology.