The Age of the Great Beliefs

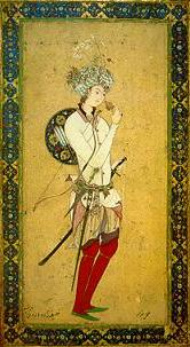

Haroun al-Rashid, Wikimedia commons

The Cross and the Crescent

The Magi

Under the Greek Seleucids (312 – 64 B.C.) Alexander’s ideal of a marriage of East and West seemed generally to be prospering. However, the whole of the rising new Levant could not be held under one scepter. Just as the Christian canon was taking shape, so too was an orthodox Zoroastrian. However, the Babylonian prophet Mani (216? – 276? A.D.), whose grandiose Manichean synthesis of Zoroastrian with Buddhist and Christian-Gnostic ideas, seemed for a time to promise to the King of Kings an even broader amalgamation of beliefs than a canon simply of Zoroastrian lore. The monarch Shapur I (ruled 241 – 272) gave Mani liberty to preach wherever he wished. When Shapur died in 272 A.D., the orthodox clergy took control and executed Mani for heresy. From then on, Zoroastrianism for the first time appeared as a fanatical and persecuting religion. During the reign of King Shapur II (310 – 379) – who was an exact contemporary of Constantine, Saint Augustine, and Theodosius the Great – the Persian reaction to what the orthodox mind calls heresy was in full play. The danger of heresy was still considered rampant two centuries later, in the period of Chosroes I (ruled 531 – 579), a contemporary of his Christian counterpart Justinian (ruled 527 – 563), whose problems and solutions were approximately the same.

Byzantium

While Classical man stood before his gods as, in a sense, one body before another, the Magian deity is an indefinite, enigmatic Power. The idea of individual will is simply meaningless for the Magian, for “will” and “thought” in man are not prime, but already effects of the deity upon him. In the Zoroastrian sector of the Magian world the key question of mythology on which the various contending sects went apart, was that of the relationship of Angra Mainyu to Ahura Mazda – the relationship of the power of darkness to the source and being of light.

For the Christian fold, on the other hand, the chief knot of discord was the problem of the Incarnation, the nature of the Mediator who entered the realm of time, matter, and sin, to save mankind. Was he man or god? This was the main issue that divided the successive councils of the Church that followed Nicaea. As these councils went on, a split began to appear between Byzantium and Rome.

The pivotal point of the Byzantine structure was the concept of the centralized state, with many separate, but interlocking institutions of government. It proceeded from the premise that the ultimate success of all government is dependent upon the proper management of human susceptibilities, rather than upon the faithful obeisance to preconceived theories and images. The state was generally regarded as the paramount expression of society, and it was taken for granted that all human activities and values were to be brought into a direct relationship to it. Justinian assumed his throne at the age of forty-five (in 527), and was to reign more than thirty-eight years. Already in the second year of his reign, he set to work exterminating all remaining pagans, and closed the University of Athens.

The Prophet of Islam

Islam is a continuation of the Zoroastrian-Jewish-Christian heritage. The whole legend of the patriarchs and the Exodus, golden calf, water from the rock, revelation on Mount Sinai, and others are rehearsed time and time again in the Koran. The basic Koranic origin legend is of a descent of both the Arabs and the Jews from the seed of Abraham. According to the Koran, Abraham and his son Ishmael built the Kaaba of the Great Mosque of Mecca.

The basic biography of Mohammed’s life was written for the Caliph Mansur (ruled 754 – 775) by Mohammed ibn Ishaq, more than a century after the Prophet’s death. And this work itself is known only as preserved in two later writings, the Compendium of Ibn Hisham (died 840 A.D.) and the Chronicle of Tabiri (died 932 A.D.). The biography falls naturally into four main periods.

1. Childhood, youth, marriage, and first call: about 579 – 610 A.D.

Born at Mecca to a family of the powerful Kuraish tribe, the child was bereaved of his father shortly after birth and of his mother a few years later. When about twenty-four he entered the service of a wealthy woman named Khadija (older than himself, twice married and with several children) who sent him on a commercial mission to Syria, from which he returned to become her husband. She bore him two sons, both of whom died in infancy, and several daughters.

2. The first circle of friends: about 610 – 613 A.D.

Mohammed and Khadija engaged in private preaching, first in the family and among friends. In the center of Mecca, their city, stood a perfectly rectangular stone hut, known as the Kaaba, containing an image of the patron god Hubal, as well as some other sacred objects, including the black stone (possibly of meteoric origin), that is today the central object of the entire Islamic world. This stone is now said to have been given by Gabriel to Abraham; and its hut to have been the house Abraham constructed with the aid of Ishmael. Even before Mohammed’s time, the whole region around Mecca was regarded as a place of sanctity, and an annual festival took place there.

Among the first converts of Mohammed and Khadija were Mohammed’s young cousin Ali, who later became his son-in-law, an older friend (though member of another clan), the wealthy Abu Bakr, and a faithful servant of Khadija’s house, Zaid.

3. The gathering community in Mecca: about 613 – 622 A.D.

There were in Mecca people enough in Mohammed’s time prepared to respond to the call of a prophetic voice. The Kuraish were custodians of the Kaaba and a leading folk of the region. The fervor of the prophet’s increasing group provoked, in time, reactions among those of the city for whom the old deities of their tribe and the prospects of trade were life concerns enough. And these presently became so strong that Islam could be thought of by its membership as a persecuted sect – with all the advantages to group solidarity and zeal that stem from such a circumstance. Mohammed, to protect his company, shipped them across the Red Sea to Axum in Christian Abyssinia, where the king welcomed them. The prophet himself, remaining in Mecca, was abused, reviled, and in deep trouble. And it was at about this time that he was joined – providentially – by a new and wonderful convert, the young and brilliant Omar. He was now, as a kind of Paul, to become its most effective leader.

At this time Khadija died. Following the mourning of Khadija, Mohammed was asked to come to Medina, to deal with a strife between two leading Arab tribes, The Aus and the Khazraj. Mohammed sent his whole community ahead, and then, in 622 A.D., made his own secret escape, together with Abu Bakr, from Mecca to Medina.

4. Mohammed in Medina: 622 – 632 A.D.

The “Emigration” or Hegira (Arabic, hijrah, “flight”) of the Prophet to Medina marks the opening of the year from which all Mohammedan dates are reckoned. In Medina, Mohammed took advantage of its position on Mecca’s trade route to the north and managed to strengthen his position militarily. Finally, having won to his side a number of the Bedouin tribes, he returned to Mecca unopposed, in the year 630. With a grand symbolic sweep he established the new order by destroying every idol in the city. However, at the summit of his victory, the Prophet died two years later.

The Garment of the Law

Allah is a product of the same desert from which Yahweh had come centuries before. As a god of Semitic desert folk, Allah reveals, like Yahweh, the features of a typical Semitic tribal deity. The first and most important of these is that of not being immanent in nature but transcendent. The second trait is a function of the first. It is, namely, that for each Semitic tribe the chief god is the protector and lawgiver of the local group, and that alone. The tendency for Semites in the worship of their tribal gods has always been towards exclusivism, separatism and lack of tolerance for other mythologies.

During the first phase of the Israelite occupation of Canaan, Yahweh was conceived simply as a tribal god more powerful than the rest. The next epochal phase of the biblical development occurred when the god so regarded became identified with the god-creator of the universe. The concept of this god of cosmic stature did not occur to the desert Habiru (later Hebrew) until they had entered the higher culture sphere of the settled civilizations. In the High Bronze Age civilizations, personality, will, mercy, and wrath were secondary to an absolutely impersonal, ever-grinding order, of which the gods – all gods – were mere agents.

In dramatic, unresolvable contrast to this view, the peoples of the Semitic desert complex held to their own tribal patrons when they entered the higher culture field. Instead of submitting their own god to the idea of a cosmic order, they made him its originator and support – though in no sense its immanent being. And he was to be known, as in the tribal desert days, only through the social laws of his solely favored group.

Certain differences come out, however, between the biblical and Koranic concepts of the group favored by God and the character of God’s law. The first and most obvious of these is that, whereas the Old Testament community was tribal, the Koran was addressed to mankind. Islam, like Buddhism and Christianity, was in concept a world religion, whereas Judaism, like Hinduism remained in concept as well as in fact an ethnic form.There is no tribe or race triumphant in the Koran, but absolute equality in Islam.

In the Moslem legal order three controls were recognized, the first being the Koran itself. Since the Koran could not cover all eventualities, the Moslem jurists had to establish other “roots”. This second type of control was a body of tradition called the “statements” (hadith). These were anecdotes about the Prophet, supposed to have been told by one or another of his immediate companions. A vast body of such statements came into being during the first two or three centuries of Islam, and the most trustworthy were collected in canonical editions – notably those of al-Bukhari (died 870) and Moslem (died 875) – which then rapidly acquired its authority. However, points of law still arose that were not covered by these two controls. To deal with these, one resorted to use of “analogy” (qiyas), which then was the third type of control.

The body of tradition (sharía, the “highway”) that has been produced through the interaction of the precepts of the Koran (kitab, the “book”), the sayings of tradition (hadith), and extensions by analogy (qiyas), is supposed to be an exact expression of the infallibility of the group (ijma, consensus) in all matters touching faith and morals. At the outset, Islam did not foresee to have a clergy to intervene between God and man. It was the consensus of the group that was supposed to have this function. However, as Islam became organized into a system, it did produce a clerical class. This was the class of the Ulama, the “learned”. Given the sanctity of the Koran and Tradition, and the necessity of a class of persons professionally occupied with their interpretation, the emergence of the Ulama was a natural and inevitable development. Ulama claimed (and were generally recognized) to represent the community in all matters relating to faith and law, more particularly against the authority of the state. With the general recognition of ijma as a source of law and doctrine, one also got – as a consequence – the legal test for “heresy”.

The Garment of the Mystic Way

The term Sunna denotes the general, orthodox, conservative body of Islam, for whom the consensus (ijma) suffices. Two other powerful movements have challenged the absolute authority of this conservative Sunna. They are, firstly, the Shi’a, also called Shi’ites (Arabic shi’i, “a partisan” (of Ali)), whose politically formulated esotericism bears an aggressive anarchistic stamp. Secondly, the Sufis (Arabic sufi, “man of wool”, i.e. wearing a woolen robe, an ascetic), in whose raptures all the normal themes and experiences of both ascetic and antinomian mysticism are embodied.

The Shi’a sect goes back for its origin to the period just after the death of the Prophet, when the question of succession to the headship of Islam was settled by a series of murders. The first Companion to be hailed as caliph – largely through the influence of Omar – was the elderly Abu Bakr, who died two years later (634 A.D.), after appointing Omar to succeed. The partisans of Ali (the Shi’a), who had married the Prophet’s daughter Fatima and fathered Mohammed’s two grandsons Hasan and Husein, were against this succession. However, Omar was doing well and his position strengthened over time. At the height of his glory the Caliph Omar was murdered in 644 by a Persian slave.

This murder opened up the whole discussion of the succession, because instead of designating a successor, Omar had appointed a committee to elect one. The committee was composed of Ali, Othman, and four others. Othman was selected, but he survived little more than a decade – slayed while at prayer in 655, under circumstances that have led many to suppose connivance from the partisans of Ali. Othman had been a member of the powerful Umayyad clan, which was an old Meccan family that for years had opposed the Prophet, but after his victory had joined his camp and migrated to Medina.

A diplomatic and military battle between the Umayyads and Ali and his sons, which the Umayyads won, and the Umayyad Mu’awija ibn Abu proclaimed himself caliph in 660. Ali was slain by a dagger in 661, after which his older son Hasan conceded victory in return for a monetary allowance. Hasan died in 669 (said, perhaps falsely, to have been poisoned). Husain, his brother, was slain in battle, October 10, 680, when he sought to unseat the second Umayyad caliph, Yazid. This date then became the Good Friday (so to speak) of the Shi’a. “Revenge for Husain” is the cry that can still be heard wailed throughout those provinces of Islam where the Shi’a lament his martyrdom to this day. His tomb, the Mashhad Husayn, at Kebala in Iraq, where he died, is for the Shi’a the most holy place on earth.

The Shi’a position is that the reigning caliphs both of the Umayyad and of the subsequent Abbasid dynasties were usurpers and that, consequently, historic Islam is a falsification: the caliph is a pretender, the Sunna deluded, and the ijma a false guide. Islam, in the proper sense of the Koran resides in the knowledge, lost to the popular community, that passed from the Prophet to Ali and has come down only in the line of the true Imams. The word imam means spiritual leader and is applied generally to leaders of the services of the mosque. According to Sunna usage, the term applies to the founders of the four orthodox theological schools, but by the Shi’a it applied only to the disinherited, true leaders of the line of Ali and the Prophet.

This line of disinherited, true leaders is known to be twelve, because somewhere between 873 and 880 A.D. the Imam then alive, Mohammed al-Mahdi, disappeared. He is known as the Hidden Imam, is still in this world, and his second coming, as “The Guided One” (mahdi), to restore Islam, is awaited by the faithful. A variant view is that the seventh Imam was the one who disappeared; still another names the fifth. These contentions have produced numerous pretenders, and consequently numerous Shi’a sects.

The Prophet’s daughter, Fatima, is revered by the whole Mohammedan world, for she was the only daughter who bore sons to continue his heritage. As daughter, wife, and mother, she personifies the center of the genealogical mystery.

The roots of the Sufi movement do not rest in the Koran, where Mohammed comes out clearly against the monastic way of life, but in the Christian Monophysite and Nestorian monk communities of the desert and, beyond those, their Buddhist, Hindu and Jain models farther east.

The Broken Spell

When the Umayyads were overthrown in 750 A.D. by the Abbasids, the capital of the now vast Islamic empire was moved to Baghdad. Arab domination of the culture gave place to an increasing Persian influence, and the Puritanism of the desert yielded to the arts of a brilliant Levantine civilization. The extent, as well as the wealth, of the empire was at its peak in the period of Harun al-Rashid (ruled 786 – 809). In the golden period of Islam, T’ang China, and the glory that was at that time India, an infinitely beautiful and promising flowering of the arts, and, with the arts, of aristocratic sensibility and civilization, threw its spell across the world, from Cordoba to Kyoto – and beyond, as it now appears, even to Yucatan and Peru.

In all these areas there prevailed the idea of a superimposed order to which the individual had simply and humbly to bow in submission and, where possible, in rapturous realization. Neither in the Far East nor in India was there any teaching in which the doctrine of free will played any part. In all those churches of the Levant where the doctrine of free will did play a part, its only virtue lay in submission to the consensus.

Charlemagne, contemporary with Islam’s Harun al-Rashid, was a kind of barbarian chieftain of the great northwestern forest. No one viewing the earth in that glorious day of the burgeoning Great Beliefs would have supposed that the seeds of thought and spirit of the millennium next to come were germinating in neither Baghdad, Ch’ang-an, nor Benares, but in the little palace school and not yet Gothic basilica of Aix-la-Chapelle (Achen). Something happened: In 1258 A.D. Baghdad was attacked by the Mongol Hulagu and his golden horde, whose brothers Mangu and Kublai Khan, were at the same time doing the same to China. India had already been disintegrated by Islam (starting with Mahmud al-Ghazni, 1001 A.D.), and a century later would be entered and again threatened by sword by the Central Asian hordes of Tamerlane (1398). The radiant dream of divinity in civilization dissolved.

Under the Greek Seleucids (312 – 64 B.C.) Alexander’s ideal of a marriage of East and West seemed generally to be prospering. However, the whole of the rising new Levant could not be held under one scepter. Just as the Christian canon was taking shape, so too was an orthodox Zoroastrian. However, the Babylonian prophet Mani (216? – 276? A.D.), whose grandiose Manichean synthesis of Zoroastrian with Buddhist and Christian-Gnostic ideas, seemed for a time to promise to the King of Kings an even broader amalgamation of beliefs than a canon simply of Zoroastrian lore. The monarch Shapur I (ruled 241 – 272) gave Mani liberty to preach wherever he wished. When Shapur died in 272 A.D., the orthodox clergy took control and executed Mani for heresy. From then on, Zoroastrianism for the first time appeared as a fanatical and persecuting religion. During the reign of King Shapur II (310 – 379) – who was an exact contemporary of Constantine, Saint Augustine, and Theodosius the Great – the Persian reaction to what the orthodox mind calls heresy was in full play. The danger of heresy was still considered rampant two centuries later, in the period of Chosroes I (ruled 531 – 579), a contemporary of his Christian counterpart Justinian (ruled 527 – 563), whose problems and solutions were approximately the same.

Byzantium

While Classical man stood before his gods as, in a sense, one body before another, the Magian deity is an indefinite, enigmatic Power. The idea of individual will is simply meaningless for the Magian, for “will” and “thought” in man are not prime, but already effects of the deity upon him. In the Zoroastrian sector of the Magian world the key question of mythology on which the various contending sects went apart, was that of the relationship of Angra Mainyu to Ahura Mazda – the relationship of the power of darkness to the source and being of light.

For the Christian fold, on the other hand, the chief knot of discord was the problem of the Incarnation, the nature of the Mediator who entered the realm of time, matter, and sin, to save mankind. Was he man or god? This was the main issue that divided the successive councils of the Church that followed Nicaea. As these councils went on, a split began to appear between Byzantium and Rome.

The pivotal point of the Byzantine structure was the concept of the centralized state, with many separate, but interlocking institutions of government. It proceeded from the premise that the ultimate success of all government is dependent upon the proper management of human susceptibilities, rather than upon the faithful obeisance to preconceived theories and images. The state was generally regarded as the paramount expression of society, and it was taken for granted that all human activities and values were to be brought into a direct relationship to it. Justinian assumed his throne at the age of forty-five (in 527), and was to reign more than thirty-eight years. Already in the second year of his reign, he set to work exterminating all remaining pagans, and closed the University of Athens.

The Prophet of Islam

Islam is a continuation of the Zoroastrian-Jewish-Christian heritage. The whole legend of the patriarchs and the Exodus, golden calf, water from the rock, revelation on Mount Sinai, and others are rehearsed time and time again in the Koran. The basic Koranic origin legend is of a descent of both the Arabs and the Jews from the seed of Abraham. According to the Koran, Abraham and his son Ishmael built the Kaaba of the Great Mosque of Mecca.

The basic biography of Mohammed’s life was written for the Caliph Mansur (ruled 754 – 775) by Mohammed ibn Ishaq, more than a century after the Prophet’s death. And this work itself is known only as preserved in two later writings, the Compendium of Ibn Hisham (died 840 A.D.) and the Chronicle of Tabiri (died 932 A.D.). The biography falls naturally into four main periods.

1. Childhood, youth, marriage, and first call: about 579 – 610 A.D.

Born at Mecca to a family of the powerful Kuraish tribe, the child was bereaved of his father shortly after birth and of his mother a few years later. When about twenty-four he entered the service of a wealthy woman named Khadija (older than himself, twice married and with several children) who sent him on a commercial mission to Syria, from which he returned to become her husband. She bore him two sons, both of whom died in infancy, and several daughters.

2. The first circle of friends: about 610 – 613 A.D.

Mohammed and Khadija engaged in private preaching, first in the family and among friends. In the center of Mecca, their city, stood a perfectly rectangular stone hut, known as the Kaaba, containing an image of the patron god Hubal, as well as some other sacred objects, including the black stone (possibly of meteoric origin), that is today the central object of the entire Islamic world. This stone is now said to have been given by Gabriel to Abraham; and its hut to have been the house Abraham constructed with the aid of Ishmael. Even before Mohammed’s time, the whole region around Mecca was regarded as a place of sanctity, and an annual festival took place there.

Among the first converts of Mohammed and Khadija were Mohammed’s young cousin Ali, who later became his son-in-law, an older friend (though member of another clan), the wealthy Abu Bakr, and a faithful servant of Khadija’s house, Zaid.

3. The gathering community in Mecca: about 613 – 622 A.D.

There were in Mecca people enough in Mohammed’s time prepared to respond to the call of a prophetic voice. The Kuraish were custodians of the Kaaba and a leading folk of the region. The fervor of the prophet’s increasing group provoked, in time, reactions among those of the city for whom the old deities of their tribe and the prospects of trade were life concerns enough. And these presently became so strong that Islam could be thought of by its membership as a persecuted sect – with all the advantages to group solidarity and zeal that stem from such a circumstance. Mohammed, to protect his company, shipped them across the Red Sea to Axum in Christian Abyssinia, where the king welcomed them. The prophet himself, remaining in Mecca, was abused, reviled, and in deep trouble. And it was at about this time that he was joined – providentially – by a new and wonderful convert, the young and brilliant Omar. He was now, as a kind of Paul, to become its most effective leader.

At this time Khadija died. Following the mourning of Khadija, Mohammed was asked to come to Medina, to deal with a strife between two leading Arab tribes, The Aus and the Khazraj. Mohammed sent his whole community ahead, and then, in 622 A.D., made his own secret escape, together with Abu Bakr, from Mecca to Medina.

4. Mohammed in Medina: 622 – 632 A.D.

The “Emigration” or Hegira (Arabic, hijrah, “flight”) of the Prophet to Medina marks the opening of the year from which all Mohammedan dates are reckoned. In Medina, Mohammed took advantage of its position on Mecca’s trade route to the north and managed to strengthen his position militarily. Finally, having won to his side a number of the Bedouin tribes, he returned to Mecca unopposed, in the year 630. With a grand symbolic sweep he established the new order by destroying every idol in the city. However, at the summit of his victory, the Prophet died two years later.

The Garment of the Law

Allah is a product of the same desert from which Yahweh had come centuries before. As a god of Semitic desert folk, Allah reveals, like Yahweh, the features of a typical Semitic tribal deity. The first and most important of these is that of not being immanent in nature but transcendent. The second trait is a function of the first. It is, namely, that for each Semitic tribe the chief god is the protector and lawgiver of the local group, and that alone. The tendency for Semites in the worship of their tribal gods has always been towards exclusivism, separatism and lack of tolerance for other mythologies.

During the first phase of the Israelite occupation of Canaan, Yahweh was conceived simply as a tribal god more powerful than the rest. The next epochal phase of the biblical development occurred when the god so regarded became identified with the god-creator of the universe. The concept of this god of cosmic stature did not occur to the desert Habiru (later Hebrew) until they had entered the higher culture sphere of the settled civilizations. In the High Bronze Age civilizations, personality, will, mercy, and wrath were secondary to an absolutely impersonal, ever-grinding order, of which the gods – all gods – were mere agents.

In dramatic, unresolvable contrast to this view, the peoples of the Semitic desert complex held to their own tribal patrons when they entered the higher culture field. Instead of submitting their own god to the idea of a cosmic order, they made him its originator and support – though in no sense its immanent being. And he was to be known, as in the tribal desert days, only through the social laws of his solely favored group.

Certain differences come out, however, between the biblical and Koranic concepts of the group favored by God and the character of God’s law. The first and most obvious of these is that, whereas the Old Testament community was tribal, the Koran was addressed to mankind. Islam, like Buddhism and Christianity, was in concept a world religion, whereas Judaism, like Hinduism remained in concept as well as in fact an ethnic form.There is no tribe or race triumphant in the Koran, but absolute equality in Islam.

In the Moslem legal order three controls were recognized, the first being the Koran itself. Since the Koran could not cover all eventualities, the Moslem jurists had to establish other “roots”. This second type of control was a body of tradition called the “statements” (hadith). These were anecdotes about the Prophet, supposed to have been told by one or another of his immediate companions. A vast body of such statements came into being during the first two or three centuries of Islam, and the most trustworthy were collected in canonical editions – notably those of al-Bukhari (died 870) and Moslem (died 875) – which then rapidly acquired its authority. However, points of law still arose that were not covered by these two controls. To deal with these, one resorted to use of “analogy” (qiyas), which then was the third type of control.

The body of tradition (sharía, the “highway”) that has been produced through the interaction of the precepts of the Koran (kitab, the “book”), the sayings of tradition (hadith), and extensions by analogy (qiyas), is supposed to be an exact expression of the infallibility of the group (ijma, consensus) in all matters touching faith and morals. At the outset, Islam did not foresee to have a clergy to intervene between God and man. It was the consensus of the group that was supposed to have this function. However, as Islam became organized into a system, it did produce a clerical class. This was the class of the Ulama, the “learned”. Given the sanctity of the Koran and Tradition, and the necessity of a class of persons professionally occupied with their interpretation, the emergence of the Ulama was a natural and inevitable development. Ulama claimed (and were generally recognized) to represent the community in all matters relating to faith and law, more particularly against the authority of the state. With the general recognition of ijma as a source of law and doctrine, one also got – as a consequence – the legal test for “heresy”.

The Garment of the Mystic Way

The term Sunna denotes the general, orthodox, conservative body of Islam, for whom the consensus (ijma) suffices. Two other powerful movements have challenged the absolute authority of this conservative Sunna. They are, firstly, the Shi’a, also called Shi’ites (Arabic shi’i, “a partisan” (of Ali)), whose politically formulated esotericism bears an aggressive anarchistic stamp. Secondly, the Sufis (Arabic sufi, “man of wool”, i.e. wearing a woolen robe, an ascetic), in whose raptures all the normal themes and experiences of both ascetic and antinomian mysticism are embodied.

The Shi’a sect goes back for its origin to the period just after the death of the Prophet, when the question of succession to the headship of Islam was settled by a series of murders. The first Companion to be hailed as caliph – largely through the influence of Omar – was the elderly Abu Bakr, who died two years later (634 A.D.), after appointing Omar to succeed. The partisans of Ali (the Shi’a), who had married the Prophet’s daughter Fatima and fathered Mohammed’s two grandsons Hasan and Husein, were against this succession. However, Omar was doing well and his position strengthened over time. At the height of his glory the Caliph Omar was murdered in 644 by a Persian slave.

This murder opened up the whole discussion of the succession, because instead of designating a successor, Omar had appointed a committee to elect one. The committee was composed of Ali, Othman, and four others. Othman was selected, but he survived little more than a decade – slayed while at prayer in 655, under circumstances that have led many to suppose connivance from the partisans of Ali. Othman had been a member of the powerful Umayyad clan, which was an old Meccan family that for years had opposed the Prophet, but after his victory had joined his camp and migrated to Medina.

A diplomatic and military battle between the Umayyads and Ali and his sons, which the Umayyads won, and the Umayyad Mu’awija ibn Abu proclaimed himself caliph in 660. Ali was slain by a dagger in 661, after which his older son Hasan conceded victory in return for a monetary allowance. Hasan died in 669 (said, perhaps falsely, to have been poisoned). Husain, his brother, was slain in battle, October 10, 680, when he sought to unseat the second Umayyad caliph, Yazid. This date then became the Good Friday (so to speak) of the Shi’a. “Revenge for Husain” is the cry that can still be heard wailed throughout those provinces of Islam where the Shi’a lament his martyrdom to this day. His tomb, the Mashhad Husayn, at Kebala in Iraq, where he died, is for the Shi’a the most holy place on earth.

The Shi’a position is that the reigning caliphs both of the Umayyad and of the subsequent Abbasid dynasties were usurpers and that, consequently, historic Islam is a falsification: the caliph is a pretender, the Sunna deluded, and the ijma a false guide. Islam, in the proper sense of the Koran resides in the knowledge, lost to the popular community, that passed from the Prophet to Ali and has come down only in the line of the true Imams. The word imam means spiritual leader and is applied generally to leaders of the services of the mosque. According to Sunna usage, the term applies to the founders of the four orthodox theological schools, but by the Shi’a it applied only to the disinherited, true leaders of the line of Ali and the Prophet.

This line of disinherited, true leaders is known to be twelve, because somewhere between 873 and 880 A.D. the Imam then alive, Mohammed al-Mahdi, disappeared. He is known as the Hidden Imam, is still in this world, and his second coming, as “The Guided One” (mahdi), to restore Islam, is awaited by the faithful. A variant view is that the seventh Imam was the one who disappeared; still another names the fifth. These contentions have produced numerous pretenders, and consequently numerous Shi’a sects.

The Prophet’s daughter, Fatima, is revered by the whole Mohammedan world, for she was the only daughter who bore sons to continue his heritage. As daughter, wife, and mother, she personifies the center of the genealogical mystery.

The roots of the Sufi movement do not rest in the Koran, where Mohammed comes out clearly against the monastic way of life, but in the Christian Monophysite and Nestorian monk communities of the desert and, beyond those, their Buddhist, Hindu and Jain models farther east.

The Broken Spell

When the Umayyads were overthrown in 750 A.D. by the Abbasids, the capital of the now vast Islamic empire was moved to Baghdad. Arab domination of the culture gave place to an increasing Persian influence, and the Puritanism of the desert yielded to the arts of a brilliant Levantine civilization. The extent, as well as the wealth, of the empire was at its peak in the period of Harun al-Rashid (ruled 786 – 809). In the golden period of Islam, T’ang China, and the glory that was at that time India, an infinitely beautiful and promising flowering of the arts, and, with the arts, of aristocratic sensibility and civilization, threw its spell across the world, from Cordoba to Kyoto – and beyond, as it now appears, even to Yucatan and Peru.

In all these areas there prevailed the idea of a superimposed order to which the individual had simply and humbly to bow in submission and, where possible, in rapturous realization. Neither in the Far East nor in India was there any teaching in which the doctrine of free will played any part. In all those churches of the Levant where the doctrine of free will did play a part, its only virtue lay in submission to the consensus.

Charlemagne, contemporary with Islam’s Harun al-Rashid, was a kind of barbarian chieftain of the great northwestern forest. No one viewing the earth in that glorious day of the burgeoning Great Beliefs would have supposed that the seeds of thought and spirit of the millennium next to come were germinating in neither Baghdad, Ch’ang-an, nor Benares, but in the little palace school and not yet Gothic basilica of Aix-la-Chapelle (Achen). Something happened: In 1258 A.D. Baghdad was attacked by the Mongol Hulagu and his golden horde, whose brothers Mangu and Kublai Khan, were at the same time doing the same to China. India had already been disintegrated by Islam (starting with Mahmud al-Ghazni, 1001 A.D.), and a century later would be entered and again threatened by sword by the Central Asian hordes of Tamerlane (1398). The radiant dream of divinity in civilization dissolved.